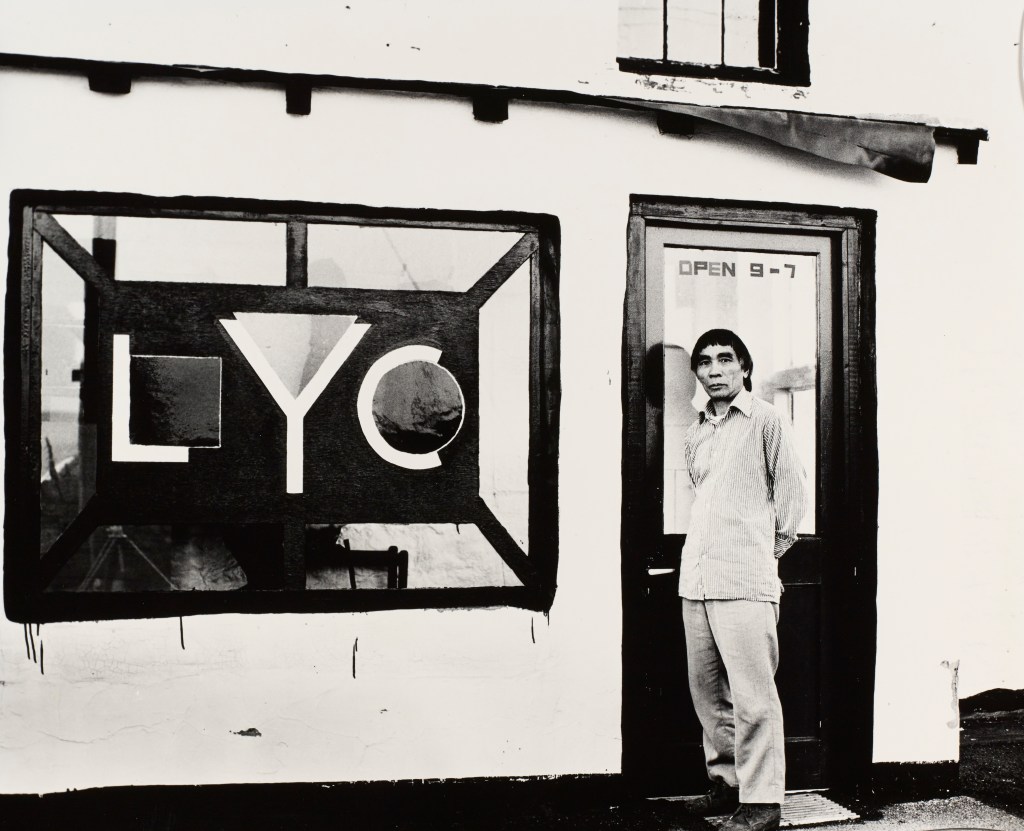

Li Yuan-chia standing at the porch of the LYC Museum & Art Gallery, featuring window designed by David Nash. Image courtesy of Li Yuan-chia Archive, The University of Manchester Library.

Li Yuan-chia (1929-94), the artist at the heart of Kettle’s Yard’s exhibition Making New Worlds, was obsessed with the ‘cosmic point’. This is the microcosm that connects us to the macrocosm – the idea that the smallest dot can make us rethink our relationship with the world and universe around us. Its apparent paradoxes, so key to Li’s artistic practice, are caught up in its very name: specific yet transcendent, minute yet infinitesimal, singular yet collective. The ‘cosmic point’ and its small circular forms roam throughout this exhibition, from the calligraphy and ink drawings Li produced at art school in Taiwan, to the large-scale installations he made in Cumbria, North West England, where he founded the LYC Museum & Art Gallery in 1972.

The LYC became a gathering space for artists and non-artists alike. Challenging ideas of the rarefied museum space, it combined gallery and studio with community rooms. It offered respite and refreshments to walkers, and featured a kitchen and a drawing machine for children, commemorated in this exhibition by Anna Brownsted’s Drawing Machine #6 (2023). Over the course of 12 years, over 300 artists travelled there to collaborate with Li and each other, and exhibit their work. Sarah Victoria Turner, one of the Kettle’s Yard exhibition’s co-curators, describes the LYC as a manifestation of Li’s ‘cosmic point’, “a place that an energy radiated out from”. As Li himself proclaimed, “LYC is Me. LYC is You.”

Anna Brownsted’s Drawing Machine #6 (2023). Photo: Jo Underhill.

When I meet Amy Tobin, another of the exhibition’s co-curators (alongside Turner and Hammad Nasar), in the Kettle’s Yard café, I ask her what first drew Li to Cumbria. (He went there to spend Christmas with a friend in 1968, and never left.) Tobin suggests that he was allured by Cumbria’s “active energy”, cultivated by artists like Winifred Nicholson, who sold Li the building that became the LYC. The museum’s location – mere metres from Hadrian’s Wall – was absolutely cohesive with his practice. The wall may have started out as a division marker (literal and symbolic) between England and Scotland, but it became a historic point of convergence: ancient and modern, manmade and natural, and different peoples and cultures. A year after the LYC opened and 15 miles east, archaeologists unearthed one of the oldest handwritten documents in Britain – a 2000-year-old birthday invitation from one woman to another. Li’s vision of friendship and hospitality was right at home.

Local maps and photographs of the LYC’s surroundings and its ancient sites are scattered throughout the exhibition space and pieces. Andy Goldsworth’s playful photographs, How to Make a Black Hole (1980) and Hazel stick throws (1980), document his interactions with the Cumbrian countryside, the artist, the wild surroundings, and the cosmic coinciding. As Tobin notes, “this is a period of artists engaging with landscape in all kinds of new and interesting ways”, for which the LYC became “a kind of hub”. She’s keen to emphasise, though, that while artists went to the LYC for the landscape, they also went there to work with Li.

How does Making New Worlds approach this collaboration? Tobin explains that as a curator, “the first thing you ask yourself is: is this a group show or a solo show?” Previously, when Li’s work was exhibited at the Camden Arts Centre in 2001, it was as a solo show, but for Tobin and her co-curators, it had to be both. Like the ‘cosmic point’, the exhibition finds the collective in the singular – hence the subtitle, ‘Li Yuan-chia and Friends’. The choice was partly about being true to Li’s work and practice, but Tobin also reminds me that “the same is true for most artists”. Part of the point was about asking, “Could you effectively tell the story of one artist in this much bigger context?”

The exhibition’s resounding answer is yes. Li’s own artworks are dispersed amongst those of his friends and collaborators, as well as new commissions from contemporary artists. Tobin reflects that the exhibition itself was built on collaboration, having been in the works since a conference in 2019. “The project grew out of each of our different interests […], but also our friendship.”

From the beginning, the show was planned with Kettle’s Yard in mind as a location. Li’s vision of the more informal, communal gallery space resonates with that of Jim and Helen Ede, the house’s creators and former inhabitants. The exhibition and permanent collection are in constant dialogue. Artists like Barbara Hepworth and Winifred Nicholson appear in both, and Li’s recurring ‘cosmic point’ finds its echo in Jim Ede’s Spiral of Stones (c.1958), or the yellow circle in Joan Miró’s Tic Tic (1927).

But Tobin is keen to point out the significant differences between the two, as well. The Edes donated the Kettle’s Yard house to the University of Cambridge in 1966, under the condition of its total preservation. The LYC, in contrast, closed in 1983, and fell into complete disrepair. David Nash’s Window for the LYC (c.1980), restored by the artist for this exhibition, is a heartbreaking reminder of the museum’s now-dilapidated state. For Tobin, the contrast between Kettle’s Yard and the LYC is important. It’s a reminder of “the discrepancy about who gets their project remembered and recovered and looked after over time”.

Our conversation shifts northwards again. (We are both from the North – Tobin is from Blackpool, and I’m from Newcastle.) For Tobin, the LYC found itself in “a region that has a very vital culture”, but one which is “not tended to in the way that arts organisations are in the South”. We talk about funding: about recent cuts in local authority’s cultural budgets, about the previous disparity in Arts Council funding within and outside of London, about austerity and its “self-reproducing cycle” of a lack of engagement. In relation to current discussions about cultural ‘levelling up’, such as the December announcement of the ENO’s move to Manchester, Tobin warns against the simple “export” of London cultural models to the North, highlighting the importance of local, accessible projects.

Though Kettle’s Yard is conceptually a perfect fit for the exhibition, I ask if they considered hosting the exhibition in a Northern cultural space. “We tried very hard to find a partner for the exhibition”, Tobin explains, but the element of luck, as well as regional disparities in resources, complicated efforts. Nonetheless, she and her co-curators remain hopeful that the exhibition could tour, or see some of its pieces go elsewhere. “Certainly, we’ve been having those conversations”. People who knew Li and the LYC have made “huge journeys” to see the show, and “it would be nice for something to happen closer to home”.

Regardless, as the ‘cosmic point’ suggests, location was both fundamental and yet transcended in Li’s practice. His art and its impact went far further than any single place. Tobin’s favourite piece in the exhibition – today, at least; “I have so many” – is Shelagh Wakely’s Toward the Inside of a Container (1979), a floor-based arrangement of broken clay and ceramic vessels which sits in the centre of one of the rooms. “It came to kind of symbolise something that I felt the show was trying to do in the end, which was bringing together something from fragments”. This is true of the exhibition literally, highlighted by the discovery and restoration of the window from the LYC, but also metaphorically, in its themes of congregation and collaboration in a divided and embattled society – no less relevant today than in the 1970s and 1980s.

Through Li, a migrant who found a home for himself, his art, and his ideas about art in Cumbria, the exhibition is an incredibly timely reminder of art’s role in forging real community. When I ask Tobin to describe the exhibition in three words, she answers assuredly: “Cosmic. Generous. Experimental.” It is the second of these adjectives that she stresses, springing from feedback from visitors and colleagues. Generosity and hospitality were so important to Li himself, who was photographed carrying a tray of homemade flapjacks around his gallery in 1976. Fittingly, then, this is the note on which the exhibition ends, with Charwei Tsai’s Ancient Desires (2023) inviting visitors to leave and take gifts from its offering bowls. What better way to commemorate this artist and his vision?

Li Yuan-chia in the gallery of the LYC Museum and Art Gallery, Brampton, Cumbria, 17 July 1976, Edinburgh Arts 1976. Courtesy of Demarco Digital Archive, University of Dundee & Richard Demarco Archive.

Quotations have been edited slightly for clarity.

‘Making New Worlds: Li Yuan-chia & Friends’ is on at Kettle’s Yard until 18 February, alongside a satellite exhibition, ‘Making New Forms: Li Yuan-chia and Friends’, at Jesus College, Cambridge.

By Rachel Rees