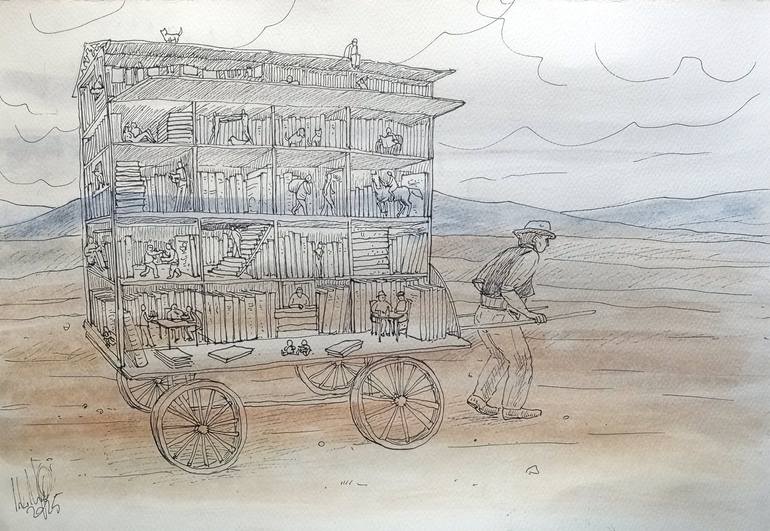

Artwork by Paolo Floriano Beneforti

In a lecture hosted by the Whichcote Society last May, Camille Ralphs shared her experience as a poet walking the Camino de Santiago. Delivered in Ralphs’s full-bodied cadence (so very her own that I no longer find it possible to read her poetry without hearing it) and dense with journal entries and metaphysical meditations and stunning verse, I thought that the lecture demanded to be dwelt upon and regretted that I couldn’t attend it again. Having lost my chance to transcribe it all for personal perusal, I decided that the next best thing would be to ask Camille for an interview.

Ralphs’s first collection of poems After you were, I am (2024), longlisted for the National Book Critics Circle Award, was widely praised for the word-alchemy, the fertile ventriloquism, and (a personal favourite, courtesy of The Guardian) the “steampunk depth” of Ralphs’s verse. She is the first woman to have served as poetry editor for the Times Literary Supplement.

Maria: You titled your lecture Alons! The road is before us, after a line from Whitman’s wonderful ‘Song of the Open Road’. Whitman’s poem ends with an address to a “Camerado”, to whom the speaker asks: “Will you give me yourself? will you come travel with me?/Shall we stick by each other as long as we live?”. Pilgrimage is a journey with an end – like a sanctuary – that is at once deeply solitary and a communing with fellow pilgrims and nature. On the other hand, the Baudelairean flaneur wanders aimlessly in a city setting, as a spectator rather than a participant amidst multitudes. Are you more of a pilgrim, or a flaneuse, or both? When you were walking the Camino, did you find yourself writing toward an imagined “Camerado” or did the meditative element of pilgrimage turn your poetry inward?

Camille: It’s hard to be a pilgrim in the city, with its millions of people and its atmosphere of laissez-faire detachment (which is other ways liberating). There’s a social contract of persistent motion, which results in irresponsibility, which lets you walk past homeless people and ignore them. (If you found a person lying in a village road, you’d always try to help them.) Or perhaps it’s the familiarity of London that’s my problem: it’s much easier to focus on each individual when there are fewer people, but I’ve also noticed that when travelling alone in foreign cities I’ve been more tuned in to others’ feelings. Perhaps it’s just that in those cases my intention is connection and discovery instead of getting through the day, so I’m more primed to interact with people. And yes, I thought about an interlocutor; but also yes, the work turned inwards. I hoped to force some kind of change, because I was exhausted with myself and tired of the ways of thinking that seemed “natural” to me. This was one of a number of recent/current projects of self-exposure – here, making myself to address an imagined future self or idealized present self, or, more than that, trying to catch up with/live up to that person.

M: You spent lockdown applying yourself to W.H. Auden’s College for Bards curriculum. On the Camino de Santiago, did you follow Waltman’s prescriptions for pilgrims?

“To undergo much, tramps of days, rests of nights,

To merge all in the travel they tend to, and the days and nights they tend to,

Again to merge them in the start of superior journeys,

To see nothing anywhere but what you may reach it and pass it,

To conceive no time, however distant, but what you may reach it and pass it,

To look up or down no road but it stretches and waits for you, however long but it stretches and waits for you,

To see no being, not God’s or any, but you also go thither,

To see no possession but you may possess it, enjoying all without labor or purchase, abstracting the feast yet not abstracting one particle of it,

To take the best of the farmer’s farm and the rich man’s elegant villa, and the chaste blessings of the well-married couple, and the fruits of orchards and flowers of gardens,

To take to your use out of the compact cities as you pass through,

To carry buildings and streets with you afterward wherever you go,

To gather the minds of men out of their brains as you encounter them, to gather the love out of their hearts,

To take your lovers on the road with you, for all that you leave them behind you,

To know the universe itself as a road, as many roads, as roads for traveling souls.”

C: One of the problems with (wonderful) Whitman is his famous longer poems’ love of subatomic similarity and mutual compassion, or their only vague attention to the untriumphant variances of experience. Perhaps if you travel alone as Whitman you can see and feel this stuff in an unclouded way, but if you travel as a young-ish woman, you can change any line-ending comma above to a question mark: you’ll probably be fine, but you might not be. Part of why I chose that title for the lecture was to worry it a bit. As for the individual points … One tree is like another and is also nothing like another. Material is infinitely various. And you go in all directions; and so does time, which is a sort of wild animal on the Camino. Shops and churches close at whenever o’clock. (In contrast, my recent US reading tour required me to be all too observant of the time, in case I missed a bus or train or flight and ruined everything; I was very much on the clock, in the sense of clocking in for work – and so, it seemed, was everybody else.) I didn’t eat as much of the orchards as I’d like, but did explore a lot of Spanish mini-supermarkets. I remember many different brightnesses of day- and twilight. And I have a newfound sensitivity to different types of road (dirt, asphalt, cobbled). The biggest regrets I have concern the other travellers I wish I’d talked to. As a writer, you protect your thinking/writing time. Sometimes that means missing out. Though I did literally take my lover on the road with me. She’s one traveller I talked to a lot.

M: Ancient philosophers walked in order to think and Romantic poets composed verse while walking. I am no poet, but I write, and whenever I relinquish my electronic devices for a while (something I try to do as much as possible), I notice my perception sharpening, my imagination increasing and the sights around me assuming renewed vividness. It seems to me that we spend much of our time asleep. But is simply “looking up” enough to see? Or does walking bring about an even keener alertness to oneself and what’s around one? What did walking the Camino do for your poetic imagination? Does the poetry you compose while sitting down have a different quality to the poetry you compose while walking?

C: Walking is meditative and subliminally generative. I don’t compose while walking, but find that the walk frees something in my mind or softly organizes it. And travel slows down time. (I’ve been reading The Magic Mountain, and Thomas Mann, in H. T. Lowe-Porter’s velvety translation, puts this very well: “Habituation is a falling asleep or fatiguing of the sense of time; which explains why young years pass slowly, while later life flings itself faster and faster upon its course. We are aware that the intercalation of periods of change and novelty is the only means by which we can refresh our sense of time […] and therewith renew our perception of life itself.”) I do feel more awake to things when “on the road”. Removal from a safe routine or customary context jolts whatever’s in the brain, unshelving things and rearranging what had seemed definitive.

M: In your lecture, you have discussed the tiredness, the aches, the trying periods of waiting, the inconveniences and discomforts that are constitutive of pilgrimage. Modern society goes to great lengths to anaesthetise human life from pain, danger, discomfort and boredom (even to the point of punishment when, say, health and safety regulations are contravened). But pain lets us know that we’re alive. Pain is also inseparable from love. In your experience, how important is pain to creation?

C: Health and safety regulations have saved me from myself, I’m sure… But yes, every light will cast a shadow, and contrast and proportion are required, as concepts, for any comprehension of the world. And for me there is an element of sublimation in poetic writing. Before I start to stuff my thoughts in the funnels of diction and form, I have to locate the particular pain, the painful question, in myself that must be worked through. Creativity, for humans at least, is largely about connecting things in surprising ways; and it’s harder to connect to others, or connect another to your work and to the world within it, these being the important secondary connections for a writer, if you can’t at least attempt to feel and so invoke their pain (or their gratitude, or laughter). The rest is just confectionery – albeit sometimes fun confectionery, and there’s a lot that I enjoy about or learn from purely playful writing. Poems can’t be always setting out to heal people, though poets are respected less and less as artists, in our moment, and increasingly aligned with politicians, therapists and teachers. (Which seems daft to me: who would want instruction from a poet, apart from another poet?)

M: Poet Edward Hirsch calls walking a “way of entering the body and also of leaving it”. How does your poetry navigate the paradox of simultaneous self-forgettal and painful embrace of the self?

Note: I say painful because when looking inward we don’t always like what we see – hence people’s widespread fear of being alone/need for a permanent exposure to people and noise.

C: I tend to express “myself”, or at least some “thing” I feel or have felt, through other voices, or even other times – i.e., at what my easily snookered brain regards as a “safe” remove. It’s almost hypnotism, finding all this real stuff coming out as soon as you can’t quite be blamed for feeling it or thinking it. I certainly don’t always like what I encounter when I look more closely at myself. One of the privileges of being an artist is that you get to do something with that discomfort. I can understand why people who have no way of transforming it require noise or substances or splashes of infatuation to pretend it isn’t there; I’ve been the same, in creatively fallow periods, and probably will be again. I’m not as enlightened as I could be.

M: Hopefully you won’t resent me for asking your take on this. As long as AI isn’t a “traveling soul” (i.e. as long as it isn’t sentient), can it write great poetry?

C: No. (Not lyric poetry, at least – it will surely be a great experimentalist within constraints, as in the OuLiPo tradition, and an obliging lab assistant to poets like Christian Bök.) Writing lyric poetry requires that funnelling of individual emotional (or intellectual) experience, emphasis on all three words, and AI’s understanding of the world – insofar as “understanding” is appropriate to say, even – is only ever mediated, communal, passively collaborative, drawing on existing and at-this-time digitized words and works produced by others. It follows patterns of reference, emphases, preferences and prejudices already established or programmed-in; it finds things useful and/or popular or else discards them, rather than proceeding with ideas that are to most of us unusable but to one person life-changing and then transforming them; it is not eccentric but utterly normy, and will never recognize the value of the individual voice. (Accordingly, its taste is terrible: its favourite poetry is that written by other AI.) It doesn’t write out of compulsion and conviction but because it has been told to do so; it risks nothing, having nothing to lose but others’ contributions. It will never be, in the Yeatsian phrase, “the finished man among his enemies”. Nor will it know what it means to be the crowd, the lonely man and nothing. The crowd – or the curated crowd we’ve fed to it – is all it is, or will be. Amen.

By Maria Viola Albano