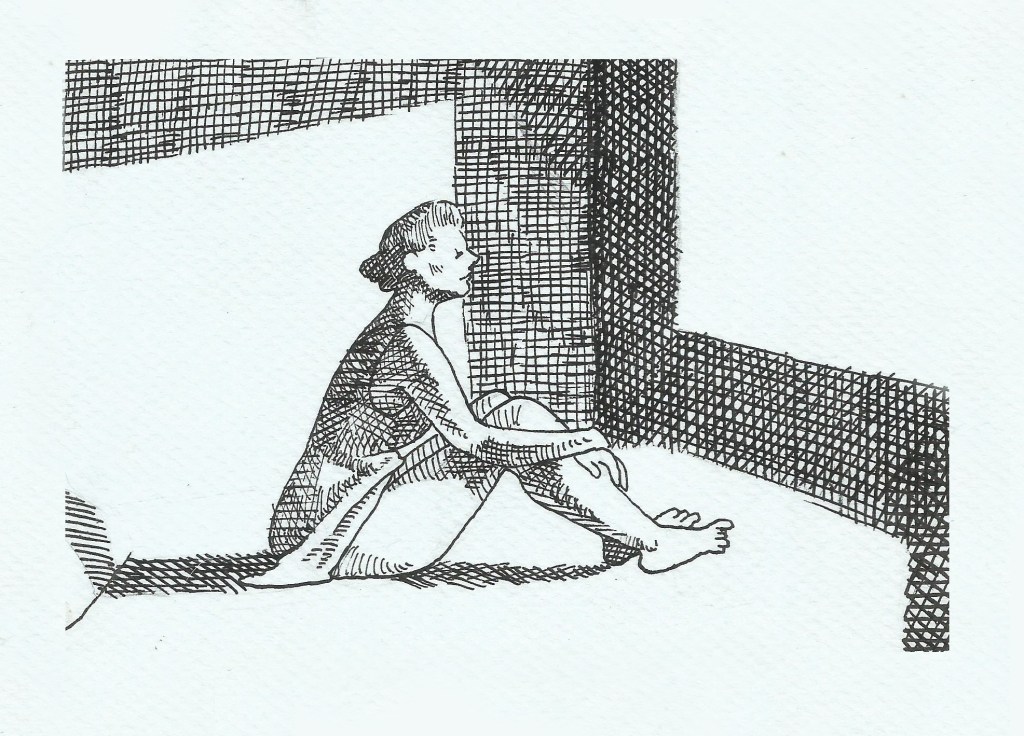

Artwork by Belén Navarro (2025)

The stories we embark upon aren’t always the ones we end up telling. Several stories compete to be at the heart of The Tower, former Times Literary Supplement editor Thea Lenarduzzi’s new memoir following the success of Dandelions (2022).

Ever since being told about Annie, a girl believed to have been quarantined in a tower for three years until her death from tuberculosis at the turn of the 20th century, T – a Kafkian anonym for Lenarduzzi – has been unable to forget about her. Initially, T’s investigations are limited to scrolling through pictures of the tower on her phone and browsing online gossip. But, as the years go by, T begins to reconstruct Annie’s tragedy in earnest, scoping out maps, newspaper articles and death certificates. Filled with trepidation, T resolves to get on a train north to visit the tower firsthand. As “fiction hardens into fact”, Annie’s fate turns out to be no real tragedy — T realises she was depending on someone else’s story to make sense of her childhood trauma.

Lenarduzzi questions whether there’s a pinpointable juncture in the business of ennobling, simplifying, or dramatising reality at which the latter becomes stripped of its status as truth and invested with the garb of fiction. She worries that fact and fiction “tip over so eagerly”. She wonders what version of a story “is real? Who decides? At what cost?”. She quotes Walter Benjamin’s pronouncement that information is “incompatible with story-telling” and that “it is half of the art of story-telling to keep a story free from explanation”. This sets up the expectation that each side of the coin – fact and fiction – will tip upward at some point. But apart from the intermezzos of Annie’s faked journal notes, Lenarduzzi never quite lets her imagination run wild — she stays firmly on the side of fact.

Lenarduzzi assembles a cast: a villain (Annie’s father Charles), his accomplices (Annie’s mother and brother), and a victim (Annie). The tower, now “an open grave”, now “a folly”, could work well as a gothic setting. Yet for all her insistence on the “murky space between” fact and fiction, Lenarduzzi no sooner ventures a theory than she has to test it against “information, references and quotations”. No matter that the blanks in Annie’s portrait strike her as “a space of mystery and possibility”, Lenarduzzi seems too much in horror of committing falsehood to exploit such possibility. Even the false premises about Annie at the root of Lenarduzzi’s obsession are someone else’s rumours. Instead of an experiment in marrying truth and narrative, The Tower comes across as a rebuttal to Benjamin: information is king and story-telling a sin.

Throughout the book, Lenarduzzi’s detective work unfolds in tormentedly self-questioning, risk-averse fashion, as colourless as the world of the filmed thoracoplasty operations she watches again and again. We follow her as she travels to Annie’s village, speaks to the locals, climbs the tower and visits the family graves – but the closer she gets to the truth, the farther the Annie of her imagination recedes. When Lenarduzzi comes to the bathetic realisation that the tower is known among the locals as where a cow called Daisy once got trapped and that Annie didn’t suffer the terrible fate she thought (the condition for Lenarduzzi’s emotional investment in her), the revelations don’t hit as hard as they should. The narrative’s build-up is too feeble for its disintegration to feel like a loss.

Lenarduzzi identifies as “more of a writer than a historian” – yet the most engaging sections of The Tower focus on extraordinary real stories of extraordinary real consumptives (John Keats, Percy Shelley, the Brontës, Anton Chekhov, Katherine Mansfield) and document her readings around the history and interpretations of tuberculosis in the 1900s, folk cures and beliefs (“lard and cheese banquets thrice a day”, “a living trout … strapped to the sufferer’s chest and left to die and decay”, “Dr Williams’ Pink Pills for Pale People”). Given Lenarduzzi’s talent in bringing the past to new life, recent news that she is currently at work on a biography of Natalia Ginzburg is welcome.

On the other hand, sections on Lenarduzzi’s motherly nostalgia, childhood asthma, or childhood sexual abuse, add little to The Tower. Lenarduzzi’s therapist tells her that writing it down “can lend a sense of validity” to trauma, but trauma alone isn’t enough to lend validity to writing. She tells Lenarduzzi that “everyone wants to share their story”. Not every story is worth publishing.

While Lenarduzzi does a good job at documenting Mansfield’s final years, Mansfield’s voice and personality are so compelling in their own right that the accompanying commentary often feels like a superfluous interference. Partly, it’s because Lenarduzzi’s observations – like “past, present and future exist in utter ignorance of each other” or “with time it becomes more of an effort to connect with the dead” – are neither shockers nor revelations. Partly, it’s that Lenarduzzi’s bids at insight-making are impaired by her lack of self-confidence, turning many of her observations into questions (“isn’t there a risk that…”, “I wonder…”, and so on). Lenarduzzi’s constant recruitment of other people – whether authorities in the field or abstract addressees – to strong-arm even the least daring of her intellectual inflections raises the question of what the point of her is. Incongruous images (yellow folders lying on a historian’s desk are compared to the “lit windows of a house at night”), lazy similes (Lenarduzzi’s yearning for “space and time” apart from her child is “like a rip current”), and unadventurous syntax make the reading experience all the more unfulfilling.

The Tower is a sometimes informative, largely artless foray into why we elevate the stories we like and mistrust the ones we don’t. Its panoply of cultural references is the best thing about it.

By Maria Viola Albano