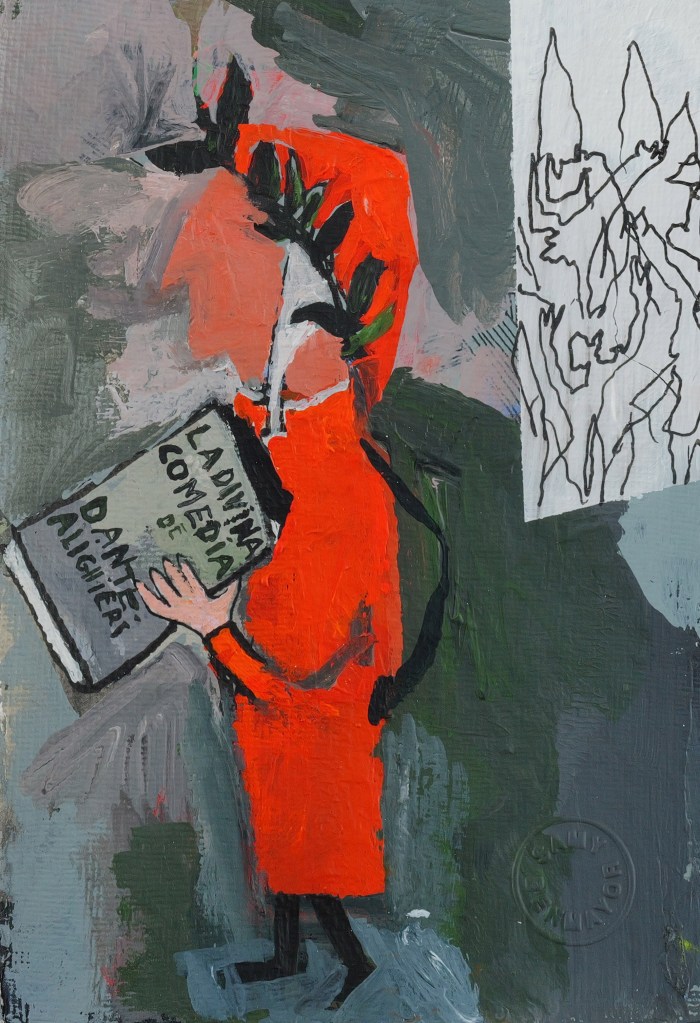

Artwork by Samy Benmayor (2025)

For a moment before bed, I consider reading a book. I roll over, fling my phone away and examine my bookshelf. Which of these suits my mood? I bought The Secret History after TikTok served me a smorgasbord of dark academia visual tropes — think cable-knit sweaters, worn loafers, an artfully stacked pile of books — promising that this was the aesthetic that the book (and, by extension, its cultured readers) would embody. I scan the other options. What about My Year of Rest and Relaxation, which got packaged for me through mood boards of sad models, cigarettes and lipstick stains after a quick TikTok scroll? Or Sharp Objects, which TikTok has essentially flattened into clips of southern gothic imagery (decaying churches, wheat fields, swampland) synced to Ethel Cain songs? Even some of the classics on my shelves — Frankenstein, Little Women — are advertised to TikTok users in similar, aestheticised ways.

A small seed of doubt begins to take root: that my reading taste for the last few years has been shaped entirely by TikTok’s book community, colloquially known as ‘BookTok’. That I should have been drawn to these books for their aesthetic mood boards, carefully curated recommendations and quick soundbites hits like a blow. Have I read anything in recent memory without having been influenced to? I cast my mind back to last Christmas, when I asked for three books I’d seen recommended under ‘weird girl lit’ BookTok. Did I rely on such a recommendation because I fit the ‘weird girl’ archetype, or is it proof of my sincere affinity with transgressive female protagonists — itself a heavily popular BookTok archetype?

Despite my discomfort at being so readily manipulated by algorithmic curation, I would be lying if I said I regret these reading choices. I don’t dislike any of the books BookTok nudged me toward — I genuinely enjoy them, and occasionally even seek out the related online content that other readers make. What unsettles me isn’t the quality of what I’m reading but the realisation that my tastes aren’t nearly as self-determined as I’d assumed. The algorithm didn’t trick me into reading bad books; it just knew exactly which good ones I’d respond to before I did.

Countless articles have examined BookTok’s outsized influence on book commerce. A quick trip to your nearest Waterstones will confirm this, with entire tables devoted to popular fiction that earned its status via BookTok itself. In an age that prioritises online virality over traditional marketing, books now circulate through recommendations on the platform instead of through press interviews, book tours and signings giving you the opportunity to meet the author. You watch a fifteen-second clip about a book without leaving your couch and immediately know what niche aesthetic it occupies. This frictionless discovery has fundamentally altered how books get consumed, published and marketed over the last few years.

Publishers everywhere clamour for the attention of ‘bookfluencers’. A 2022 Slate article lamented the ‘trope-ification’ of the publishing world as online recommendations are increasingly tied to various identifiable tropes in writing. Readers looking for books in the ‘romantasy’ genre – a hybrid of romance and fantasy – can find out whether their next reads feature ‘enemies to lovers’, raunchy knife fights, scandalous love triangles, faerie princes or marriages of convenience. Books which do possess these tropes are thus given greater attention, with titles circulating around the author and potential live action adaptations. By capitalising on this demand for specific niche genres, the publishing industry works with influencers to promote titles that fall into these categories.

Authors such as Sarah J. Maas exemplify this phenomenon: BookTok transformed her from a successful author into publishing royalty, with her A Court of Thorns and Roses series becoming a BookTok sensation years after its 2015 release. Her sales jumped 161% in one fiscal year, helping drive Bloomsbury’s consumer division sales up 49%. The relationship works both ways: Bloomsbury runs major promotional campaigns that drive word-of-mouth recommendations, particularly through TikTok and Instagram, while the platform’s algorithm ensures these books reach receptive audiences. The feedback loop between algorithmic distribution and strategic publisher investment has fundamentally reshaped how books become bestsellers. These days, viral success isn’t accidental but the result of publishers identifying and capitalising on algorithmically-driven reader appetites that already exist.

I believe that encouraging reading is fundamentally good, even though I bristle at eye contact with ‘romance’ titles whenever I enter a bookstore. Growth in the industry, no matter how tied to genre conventions and predictable themes, cannot but improve today’s reading-averse, intellectually lazy landscape. They’re reading —and that matters. Much has been written about how, with the advent of the smartphone, we have entered a ‘post-literate society’ in which people are reading and thinking critically less. The community that BookTok has provided for young people post-pandemic is important, offering an online space that introduces an entire cohort to the everyday, accessible pleasures of reading in all forms. Shouldn’t we be celebrating its role in making reading culturally relevant again, rather than scrutinising its authenticity as a cultural phenomenon?

The answer is complicated. By pushing books that fit into specific, marketable genres, publishers make it increasingly difficult to find information or buzz around books that do not align with the popular conventions of romantasy or ‘new adult’ (an emerging genre aimed at those aged between 18-25). The same titles are advertised repeatedly, along with so-called ‘hidden gems’ – such as Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier – that are anything but ‘hidden’. As with many internet communities, there comes a pressure to outdo others: bulk-buying, binge-reading and reading challenges are often used as methods to boast about the number of books you have read in a year. This reduces reading to a kind of performative competition rather than a passion or intellectual hobby.

Writers, in turn, are pressured to use BookTok to gain attention for their work, something antithetical to creativity and daring. That social media is used to market books is nothing new; but many new authors must now sell their work in the most palatable ways for new readers, prescribing to the niche tropes and genres that gain the most buzz online. This can come across as insincere, suggesting that they have written with the algorithm in mind. Plus, it’s hard to tell whether some books are being written for creative purposes or to slot into BookTok’s algorithm-friendly content. Books that do not employ popular, BookTok-endorsed tropes aren’t awarded with as much promotion or attention as those that do. As a result, our bookstores and shelves are filling up with tropified novels and popular works that picked for us by BookTok users.

But all is not lost – breaking from the chains of traditional BookTok recommendations is possible. Many online users encourage reading widely and emphasise the importance of reading as an intellectual movement. They promote titles that are perhaps not algorithm friendly, but still incredibly enjoyable reads – such as Colin Walsh’s Kala, a fantastic thriller that does not get much online attention, albeit from some smaller creators. If, however, one still longs for online alternatives to BookTok, there are popular online book clubs that champion authors of lesser known works, like Dua Lipa’s Service95 book club or Kaia Gerber’s Library Science, both featuring among other things interview authors on their writing process. Recommendations can also be found in YouTube videos and blogs on Substack providing in-depth analysis of novels.

I find that word of mouth remains the most reliable way to discover books worth reading, especially when talking to people who share similar tastes and sensibilities. Even discussing books with somebody who gravitates toward genres you’re not used to ensures that you come upon texts you would never have considered independently and might end up broadening your perspective. It’s easy to dismiss algorithm-driven recommendations, but it’s equally easy to disregard genuine human curation that happens to challenge your existing preferences.

But whether they happen on TikTok, in book clubs or over coffee, encouraging conversations about reading may be the most powerful tool we have against an increasingly ‘post-literate’ world. These discussions keep books culturally alive, reminding us that reading isn’t a solitary act of consumption but a shared experience that sustains intellectual curiosity in an age of distraction.

By Rania Sivaraj