Munch’s most famous portrait is a portrayal of anguished anonymity. ‘The Scream’ (1893) is the work of Munch the outsider and expressionistic visionary, an artist who was traumatised by the early deaths of his mother and sister and who spent much of his adult life in self-imposed exile. But this side to Munch is superimposed by a much more worldly view in the National Portrait Gallery’s exhibition. Small but punchy, it is the first in the UK to focus on Munch’s portraits, and it builds a convincing case for Munch as a man of the world.

Though he received limited formal training, portraiture ran in Munch’s blood – his grandfather, Jacob Munch (1776–1839), was one of the foremost Norwegian portrait painters, and Edvard (1863-1944) was encouraged in his artistic pursuits by his aunt and primary carer, Karen. The earliest works in this exhibition are familial and small in scale, but Munch’s scope quickly expanded, blossoming amid the hedonism of the bohemian scene of Kristiania (now Oslo). It was here that he began to explore ‘soul painting’ (painting that was reflective of his own psychological and emotional state), creating works which shocked the establishment in their stark portrayal of taboos from infant mortality to extramarital sex.

While frequently dismissed by critics as ‘insane’, Munch’s style developed in scale and confidence as he obtained lucrative commissions from European patrons. He spent an influential year in Paris in 1889, where he learned much from Henri Toulouse-Lautrec, Paul Gauguin and Vincent Van Gogh. But it was in Berlin that Munch created his most iconic pieces, including ‘At the Deathbed’ (1895) and his Frieze of Life series (1902). Much of his time was spent drinking in the Black Piglet, a haunt that drew to its doors an international circle of writers, artists and critics, including the Swedish playwright August Strindberg and Danish writer-painter Holger Drachmann. His controversial and increasingly symbolist paintings were shown frequently – in fact he was one of the most exhibited artists in Europe in the early years of the twentieth century – and Munch left a visual legacy of emotional intensity which would help to birth Expressionism. After a mental breakdown in 1908, Munch gave up drinking and returned to Norway, where he was welcomed with open arms as an artistic visionary and offered large commissions at sites as varied as chocolate factories and universities. Despite being classified as a degenerate artist, upon his death in 1944 Munch was given a state funeral in Nazi-occupied Oslo and the city subsequently took over the bulk of his estate.

Seated Model on the Couch, Birgit Prestøe, Edvard Munch, 1924 © Munchmuseet. Photo: Munchmuseet | Sidsel de Jong.jpg

You won’t find Munch’s portrait of Friedrich Nietzsche in this exhibition, but the philosopher haunts the cnvases nonetheless. Older than Munch by some two decades, Nietzsche had also suffered from a childhood racked by familial bereavement and collapsed religious faith. There is a degree to which Munch’s striking male portraits are an embodiment of Nietzsche’s Selbstüberwindung; the Übermensch who rises above circumstance and difficulty through realising a will to power. The two never met, but Munch painted Nietzsche’s sister, and created a portrait of the philosopher in 1906 for his main patron, Ernest Thiel, who had been the first to translate Nietzsche’s works into Swedish.

Munch’s full-length study of Thiel is among the best in the exhibition. The sketched lines of his lower body give a Hockney-esque modernity to the composition and emphasise his powerful stance – Thiel was also one of Sweden’s wealthiest men, and his financial backing helped to establish Munch as a great painter of his generation. The abstract rush of sea-toned strokes around Thiel’s head suggests a sort of intellectual hum, but this is equally the product of incompletion. During the sitting, a confrontation arose which left Munch so angry that he tore through the canvas with his brush. This violence is imperceptible, but there exists a haughtiness to Thiel’s expression that might understandably whip a passionate man like Munch into a storm. Usually, Munch preferred to monologue through his sittings, so as not to enter into distracting discussions of this kind.

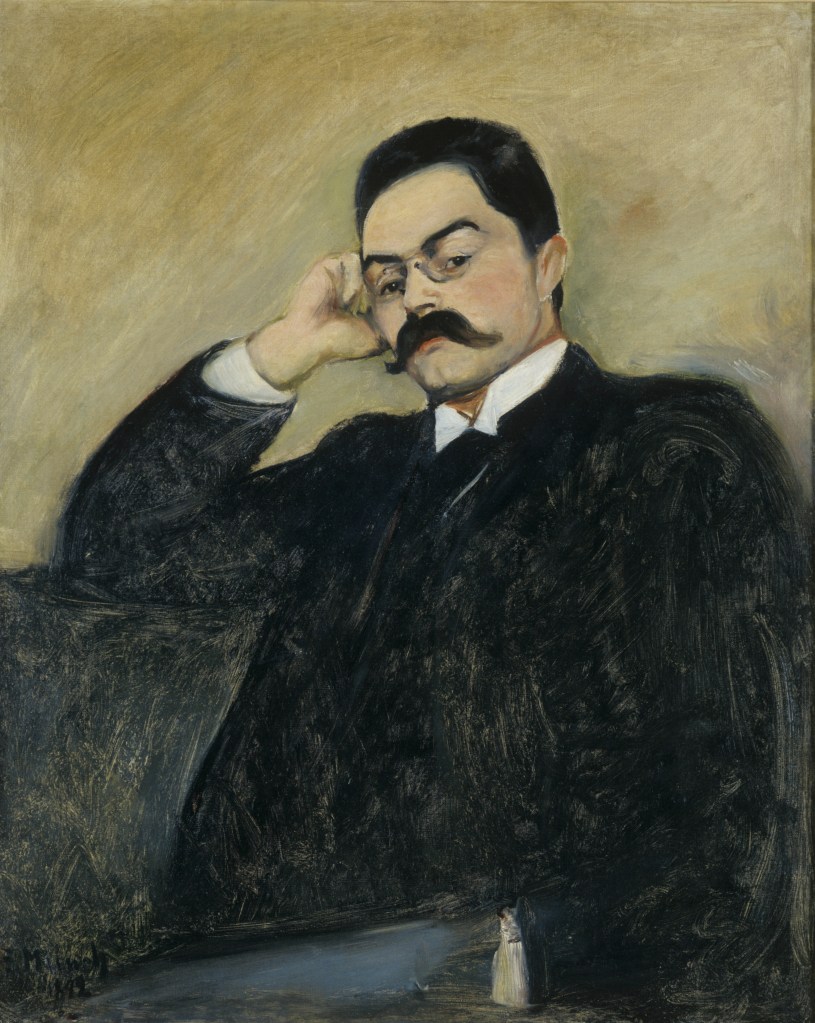

Nietzsche’s contemporary legacy is tinged with the influence his ideas had on National-Socialism’s catastrophic eugenic theories. But Munch encountered Nietzsche decades before the radicalisation of German politics in the 1920s and 30s. He was painting during a time when Jewish individuals held prominent sway in the intellectual and cultural sphere in Germany, and many of them were deeply imbued with Nietzschian thought. One such man was Felix Auerbach (1856-1933), a professor of Physics at the cradle of German philosophy – Jena University, where he and his wife were influential members of the intellectual and cultural elite. He met Munch at the Nietzsche Archives in Weimar, and commissioned this portrait in 1906. It is astoundingly confident: half-length, Auerbach is figured wielding a cigar, rosy lips slightly pursed and overhung by a fertile moustache. Munch’s well-oiled opaque strokes and crimson background recall the vibrancy of Van Gogh or Gauguin, and there’s nothing quite like it for personality or style in the show. This liveliness is tragically intensified by Auerbach’s biography: in 1933, he and his wife took their own lives following Hitler’s appointment to Chancellor.

Felix Auerbach, Edvard Munch, 1906 © Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent vanGogh Foundation).

The strength of Munich’s societal portraits comes from their intellect and professional confidence – men who are equally at home in boardrooms, bordellos and bookshops. This makes the paintings palpably modern, but they also hark back to an earlier tradition of Elizabethan and Jacobean court portraits of humanist politicians. Kenwood House’s Suffolk Collection contains some excellent examples of these by William Larkin; he painted Lord Thomas Howard de Walden, a naval captain during the Spanish Armada who also built one of the most remarkable houses of the period, Audley End; or Edward Sackville, who was a leading voice in James I’s Virginia Company and also helped to found West End theatres. While the costumes have been significantly stripped back in the intervening centuries, Munch’s brushstrokes and fleshed-out rendering of their forms resonate with the fullness of seventeenth century forebears.

While the traditional upper-class subjects of 19th century portraiture dominate his corpus in this exhibition, Munch rebelled against the traditions of formal portraiture in painting his drinking companions too. His full-length study of Karl Jensen-Hjell (1885) dignifies the shabbiness of his friend with his up-turned nicotine-hued beard and eyes half-hidden behind glinting spectacles. It is one of Munch’s earliest large-scale works, and was deemed a ‘travesty of art’ when it was first shown in Norway. Hans Jaeger, king of Kristiania’s bohemian scene and a vehement nihilist, smoulders in a rugged blue overcoat behind a half-drunk glass. More salubrious still is ‘Tête-à-tête’ (1885), one of Munch’s ‘couple portraits’ which delves into the hidden worlds that exist between partners. Here, a haze of inebriation blurs the features of a woman who faces out, her lips glowing animatedly and eyes turned towards a male figure profiled on the left. There’s an oil of Strindberg (which the playwright hated), a striking lithograph of Ibsen’s head, and another almost twinkling depiction of Mallarmé, which was commissioned by the poet a year before his death. Munch’s world is peopled by low life and national heroes alike, and is wonderfully complimented by a small (and free) exhibition on Munch’s Polish contemporary Stanisław Wyspiańksy on the floor above. Wyspiańksy’s charcoal and chalk drawings of his family and associates are remarkably vivid, capturing the creative intensity of many of the leading figures in Poland’s artistic avant-garde at the turn of the century. Both the exhibitions revel in the cultural stimulation made possible by pan-European collaboration and the interconnectivity across art forms in this period.

Hans Jaeger, Edvard Munch, 1889. Oil oncanvas. © Nasjonalmuseet for kunst, arkitektur og design, The Fine Art Collections. Photo: Nasjonalmuseet/BørreHøstland.

Tête-à-tête. Edvard Munch, 1885. Oil on canvas. © Munchmuseet. Photo: Munchmuseet / Halvor Bjørngård.

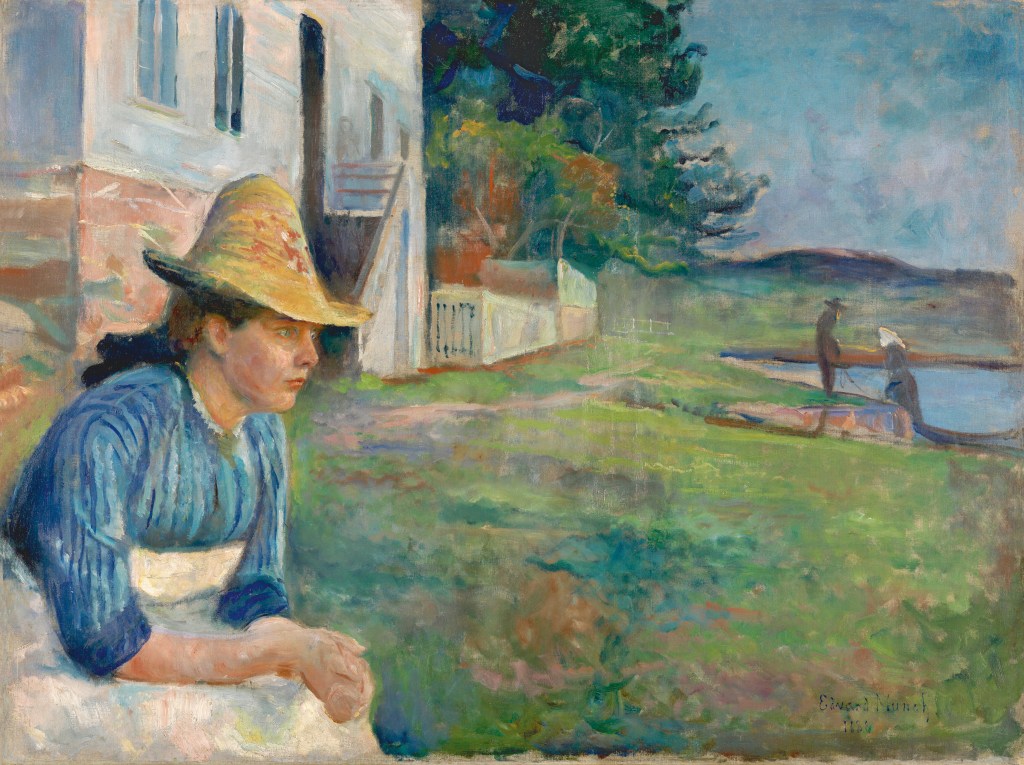

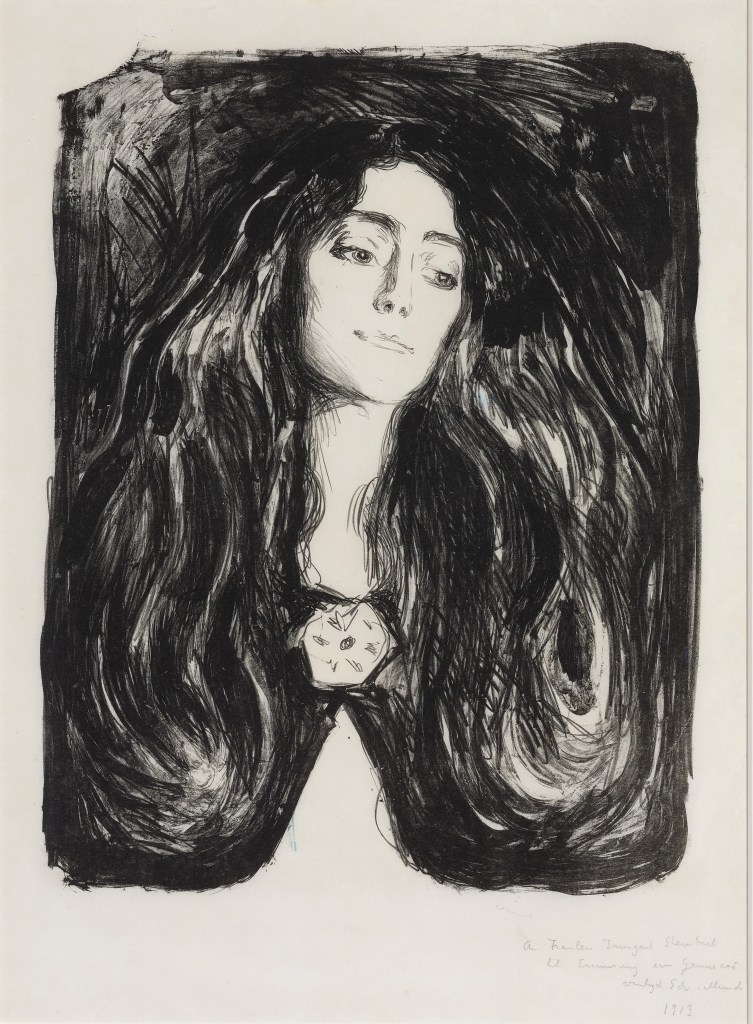

Fin-de-siècle representations of women are among the most overdressed of the century, incessantly allegorised into sexual or spiritual symbols, and often dwarfed by overbred hounds or frothing hats. However, I will admit that I am drawn to the theatrical feminine, and would have liked a few more of Munch’s symbolist women in this exhibition – his ‘Madonna’ (1894) for instance, would have provided a welcome nod to Munch’s engagement with the Viennese Secessionists and his frequent depiction of fallen women that caused scandal early in his career. The female portraits we are offered here tell a varied tale. There are two striking canvases of his sisters, both painted gazing out on to a spring-like Norwegian landscape. Theirs are among the most nuanced portraits in the exhibition, primarily because they are not depicted in confrontation with the artist, but more simply observed by him. The most prototypical femme-fatale comes in the form of ‘The Brooch’ (1902). A lithograph of Eva Mudocci (1872-1953), a Brixton-born violinist, we know little of her relationship with Munch. Her black hair luxuriates around the page in an ouroboros of intense mark-making, framing her doe-eyed face and the clock-like brooch at the nape of her neck. She represents Munch’s power as a graphic artist, and the monochromatic works like this and his ‘Self Portrait with Skeleton Arm’ (1895) are among the strongest in his entire œuvre.

The Brooch. Eva Mudocci, Edvard Munch,1902. Lithograph. © Private collection, courtesy Peder Lund.

Time and time again in these portraits we see the tension between Munch’s realism and experimentalism. While he vividly captures the intellectual thrust of Europe’s elites, his desire to evoke a feeling which transcends the flesh produces surprising details. My favourite of these is in Munch’s portrait of his lawyer, Thor Lütken (1892), on show in the UK for the first time. It is an arresting piece, not least because of its sitter’s impeccable facial grooming, but more so because of a smudged, almost imperceptible mirage on what ought to be Lükten’s cuff: it is a couple, side by side, on the edge of a moonlit lake. One is in bridal white, the other barely visible, a black smudge who might be embracing her. Romance, mystery, love, and death are visible on the very surface of this portrait of professionalism. It was painted as Munch made his commitment to soul painting, and it reminds us of his intention to render vivid the too often suppressed currents of human emotion. Stanislaw Przybyszewski,writing in the first book published on Munch in 1894, described his style as ‘a painted philosophy’. Writing over a hundred and thirty years later, I can’t describe it much better than that.

Thor Lütken, Edvard Munch, 1892. Oil on canvas. Private Collection. Photo: Munchmuseet / Sidsel de Jong.

The NPG’s Edvard Munch Portraits ends June 15.

By Iris Bowdler