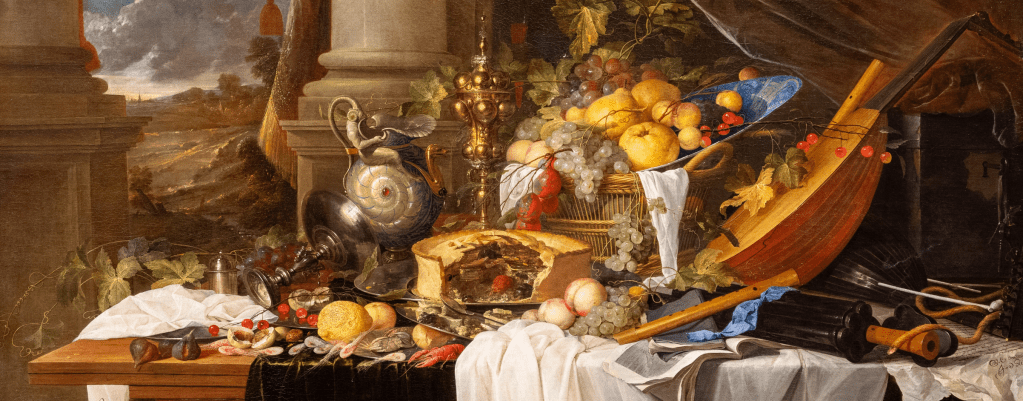

Jan Davidsz de Heem, A banquet still life, 1643, Oil on canvas. Frederick Iseman Art Trust LLC. Photograph © Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge

***

To dig for wealth we weary not our limbs;

Gold, though the heaviest metal, hither swims;

Ours is the harvest where the Indians mow;

We plough the deep, and reap what others sow.

– Edmund Waller, Panegyric (1655)

Since October, the Fitzwilliam Museum has played host to an exhibition of Dutch artist Jan Davidsz de Heem’s quartet of still-life paintings, on display together for the first time since the seventeenth century. The exhibition, entitled “Picturing Excess”, brings the four paintings together to prompt a timely reflection on greed and overconsumption – issues which are as pertinent today as they were in the Dutch Golden Age.

Stepping into gallery fifteen of the Fitzwilliam, you are immediately met with the enormity of each painting in de Heem’s headlining quartet. It’s an enormity amplified by the smaller works surrounding it, a decision no doubt made in an effort to highlight the grandiosity of the quartet by way of comparison. Unlike the smaller paintings in the exhibition, Picturing Excess’ main quartet is not intended as a simple artistic exercise, a modest record of quotidian domestic scenes, or a picture of restraint; they are paeans to the owners, commissioned to celebrate and reflect not only their personal wealth, but, by extension, the strength, prosperity, and international reach of the Dutch colonial empire, which facilitated the movement of the pictured exotic goods and treasures from around the world. As far as exhibition titles go then, this one is successfully precise: excess is perhaps the best description possible. In both their size and content, each of de Heem’s paintings is intended as hyperbole on canvas.

Painted in the pronkstilleven style, these hyperbolic pictures of consumption are depicted by an overflowing smorgasbord of sumptuous foods and luxury goods, most likely acquired through the operations of the Dutch East India Company. Exotic fruits, lobsters, shells from tropical waters, gold ornaments from the Indian subcontinent, Venetian glass and porcelain from China, large terrestrial globes, fine instruments, and the latest scientific apparatus litter the scene in what is an intentionally ostentatious display of not just wealth, but excess. The extravagance is woven into the details. A tray of lemons, as featured in Still Life in a Palatial Setting, may be nondescript to modern viewers of the paintings, but would have been a clear symbol of the owner’s financial prosperity in the seventeenth century: the Dutch climate being incompatible with the growth of lemons, the fruit would likely have been imported from the Mediterranean – a costly purchase wrought with political difficulty due to the ongoing Eighty Years War between the Spanish and Dutch Rebels.

However, beneath the superficial panegyrism and aesthetic displays lies a more critical undercurrent; Pronkstilleven, a subgenre of Vanitas painting, is a fundamentally allegorical art form, and De Heem’s still-life compositions can also be seen to convey moral warnings about greed, the fleeting nature of material wealth, and the dangers of excess leading to corruption and spiritual decay. These religio-philosophical anxieties were at the forefront of moral thinking in the seventeenth century, provoked by the financial and material success of the Dutch Empire, which in turn had led to immense economic growth, overseas expansion, and cultural flourishing. Within the compositions, motifs like the blue ribboned watch, which features concurrently in all four paintings, serve as a memento mori, pointing to the transience of life. Exotic fruits too, subject as they are to quick decay, symbolise that same transience, serving as a stark reminder that material wealth and luxury items do not always endure. On my visit to the Fitzwilliam, I overheard a conversation between a viewer and a security guard contemplating the amount of fruit which would have been wasted in the long creation of these still lifes. Whether or not they were eaten after fulfilling their shifts as the objects of these paintings is not known, but the expenditure required to capture them in painting speaks not only to the wealth of the owners but also the wastefulness of the creative process.

These fruits are but one example of the many gestalt switches that litter the paintings – aspects which flit between the celebratory and the critical. To this end, de Heem’s depictions of excess can help us, as contemporary viewers, to reflect on our own consumption habits in the twenty-first century. This practice may teeter into the forcefully anachronistic, but there is nevertheless a value in seeing the paintings through a contemporary lens, and there are several aspects to the paintings which we can only now understand as critical, analysing them as we do with a retrospective eye. Applying this connection between colonial excess and modern-day overconsumption helps us to think more ethically about our relationship to purchasing, and in this regard, de Heem’s paintings speak across time to offer particularly useful insight for the present day.

A prominent example is the portrayal of the enslaved boy in Still Life with Boy and Parrots, whose inclusion in the painting would have served, in de Heem’s time, as a symbol of the owner’s wealth and status, rather than a criticism of slavery. Emerging from behind a column and reaching for a bunch of grapes on the table, de Heem draws a parallel between the boy and a monkey sitting on the celestial globe who has already stolen some. Such mirroring reflects popular racist theories of the time, which aligned people of colour with animals to explain their primitivity and, through this equivocation, justify slavery. In the context of the painting, this comparison not only dehumanises the enslaved boy but reduces him to just another commodity, no different to the other exotic pets that populate the painting. It is only through our modern eye that we might view in the boy not a celebration of the owners’ wealth, as was its original intention, but a way to critically examine the artistic depictions of a slave trade that perpetuated racist theories and reduced humans to commodities.

Jan Davidsz de Heem, Still life in a palatial setting, 1642. © UK Private Collection

Similar “gestalt switches” recur throughout the quartet. In the foreground of Still Life in a Palatial Setting, an assortment of polished shells lay scattered atop a wooden stool. As explained in the Fitzwilliam’s accompanying label, these shells, sourced from tropical waters and admired for their shape, colour, and patterns, were thought to have been gathered, cleaned, and polished by indigenous people who did not substantially profit from their trade with the Dutch East India company. While this was not likely a concern for customers or viewers of the painting in the seventeenth century, we may interpret them, with a modern eye, as illustrative of the exploitation of workers – an issue that persists today, most notably in the practice of fast fashion. Indeed, the act of showing off these exotic, luxury goods without considering the human labour and exploitative practices involved in their production and delivery is characteristic of Marxian commodity fetishism, and echoes precisely the same behaviour that governs our relationship to commodities in the present age. As Marx explains in Das Kapital, “fetishism” in this context ascribes an intrinsic value to objects which neglects – and indeed, obscures – the means of production and, in particular, any significant malpractices associated. This is an ignorance which has become commonplace in our own relation to products and services, where the appeals of ease, low costs, and accessibility have inhibited our desire for ethical consumption.

More broadly, these issues speak to a present age obsessed with consumerism and overconsumption. In part due to the mass industry of cheap labour, and the accessibility of produce it generates, those of us who live in the privileged West may be able to acknowledge that we live in a time of need and plenty. On the one hand, vast online catalogues like Amazon, Temu, and Alibaba have radically improved access to a wider variety of purchasable commodities and services than in any period in our history. Combined with the efficiency and reach of international trade routes and supply chains, something as previously luxurious as a plate of lemons has now become trivial to the point of banality. As such, we often find that our lives, like De Heem’s still-life paintings, are filled with excess – our homes and spaces are littered with items that were bought on a whim, because we were influenced to do so, or simply because they were available. On the other hand, this availability has made us increasingly oblivious to the harmful practices which enable it – not only with regards to its production, such as cheap labour, exploitation, poor quality, and the use of harmful materials to reduce costs – but also with regards to its environmental, political, and ethical consequences. More worryingly, this rise in individual purchasing power has coincided with a rise in appetite, such that no matter how much we buy, our desire for more items can never quite seem to be satiated, and we remain in a constant state of need. Much as it was for the Dutch patrons, for modern day consumers too, objects symbolise wealth and status, and we are obsessed with showing off our possessions and creating our own paeans to celebrate our wealth.

Yet, these paeans take a uniquely different form in the twenty-first century. This is in part due to the changing nature of Art patronage. As stated by Nick Hackworth for Art Basel, the contemporary ‘global art scene [is] supported, by and large, by private collectors.’ Art patronage today, is more about collection than production, and to this end, as Irene Kim, Art Basel’s Global Head of VIP Relations, has observed, in the past decade, there has been an observable shift in focusing on the mission and philosophy behind a collection, rather than the value of its content. This in turn has also led to a reflection on ethical sources of funding, particularly from private and corporate sponsors. As Hackworth notes, ‘[t]he artist Nan Goldin’s successful PAIN campaign to stop cultural institutions accepting donations from the Sackler family in relation to the OxyContin opioid scandal, and various efforts to block Big Oil’s sponsorship’ exemplify the art world’s increasing focus on ethical art patronage and further reflects a move towards funding, supporting, and curating collections which champion underrepresented voices within the art world and provide a platform for social and ecological issues. In light of this new environment of patronage, the commissioning of such paeans to personal wealth by a wealthy elite class would most likely be considered ostentatious, arrogant, and tone-deaf by current ethical standards.

Glenstone Museum, Potomac, Maryland. © Barbara Kruger. Courtesy Mary Boone Gallery, New York. Photo: Tim Nighswander/Imaging4Art.com

And yet, such pieces may serve a larger purpose. As distasteful as the celebratory aspects of de Heem’s quartet may be to contemporary viewers, the paintings nonetheless serve a critical function in encouraging a reflection on the dangers of overconsumption and excess. If the commission and exhibition of pronkstilleven like de Heem’s quartet are avoided due to bad taste, how might contemporary art best reflect the paradoxical states of need and plenty which also define twenty-first century consumerism? Indeed, more recent artistic attempts to criticise habits of overconsumption – like Barbara Kruger’s Untitled (I Shop Therefore I Am) – are as common in the art world as personal paeans to wealth are on social media, but what distinguishes de Heem’s paintings are their ability to incorporate both the critical and celebratory into a singular representation of consumer habits. In doing so, Picturing Excess allows us to recognise and think critically about the universal impulse to showcase wealth, and its underlying shortcomings, in both the Dutch Golden Age and the present day.

By Chiraag Shah