Mark Mann, Fig Leaf. A1 Giclée print (60×85 cm). Photograph: © Mark Mann and Rebecca Mowse.

***

Anyone au courant with discourses in Classics (a rose by any other name), particularly those encircling its art historical arm, will have become attuned to the recent rise in color consciousness in the field, most of all concerning classical statuary. The gist has been that these ‘colorless’ sculptures, long lauded for their marmoreal whiteness, were not always so; in reality, they were almost painfully polychromatic to the eye, giving viewers an unrelenting synesthetic fill. The chromatic turn of the ‘classical’ has fueled monographs and op-eds alike, so it is fitting, perhaps, that Norfolk-based artist Mark Mann’s vibrant exhibition has alighted upon Cambridge’s Museum of Classical Archaeology, a collection which itself has taken an increasingly colorful turn over recent years.

‘A Room of One’s Own’ is, in Mann’s own words, “a collection of works inspired by the bravery of the queer interior.” The queer interior in question is one belonging to a time before homosexuality’s decriminalization (1967; amended variously thereafter) and amidst the Bloomsbury Set’s flourishing. News to me was the celebrated phrase “a room of one’s own” not being Virginia Wolf’s own coinage; rather, it was expressed by Lytton Strachey, who penned it in a tender billet-doux to Duncan Grant. The two sought a space that was uniquely theirs, one in which they could craft a life, jewellike in its brilliance, beyond the eyes of a vituperatively heteronormative society. Without the license to live as they desired publicly—for theirs was a world in which Douglas’ apophatic “the love that dare not speak its name” and peccatum illud horribile, inter Christianos non nominandum (“that horrible sin not to be named among Christians”) dogged the steps of queer individuals—the privacy afforded by the oracular interior was something of a canvassed diptych, half blanche and half palimpsest. By way of the former, demimondes could meticulously curate their kaleidoscopic identities. The latter let heteronormativity be iconoclastically interpreted and overlayed.

When mingled with the classical—the agendas on display ranging from Ursprünge in liberalism to shrines of arch-conservatism—Mann’s exhibition squares queerness, antiquity, aesthetics, and embodiment to hone in on how queer life is theoretically and hermeneutically productive. The room in which ‘A Room of One’s Own’ is situated strategically conjoins exhibition and viewer both under the aegis of queer (un)historicism, privileging anachronism as the guiding force for reimagining how we ‘sex’ and ‘gender’ the past, dangling—stranding, even?—the peruser between the promise of an instrumentalized antiquity and an uncertain, but possible, modernity, much as it did for those living in the era under scrutiny. We ought to imagine such people as continuously re-inscribed between public and private histories, between innuendo and truth, between marriages lavender and blanc. On this reading, being queer was—and still is, by many metrics—eternally untimely and demanding, deposited under a pristine veneer that belies such vagaries. “I enjoy the idea,” Mann declares, “that I use finely-crafted facades to conceal ugly realities within my design work.”

Mark Mann, Penis Bowl (Small). Terracotta, gold (10.5x13x11 cm). Photograph: © Mark Mann.

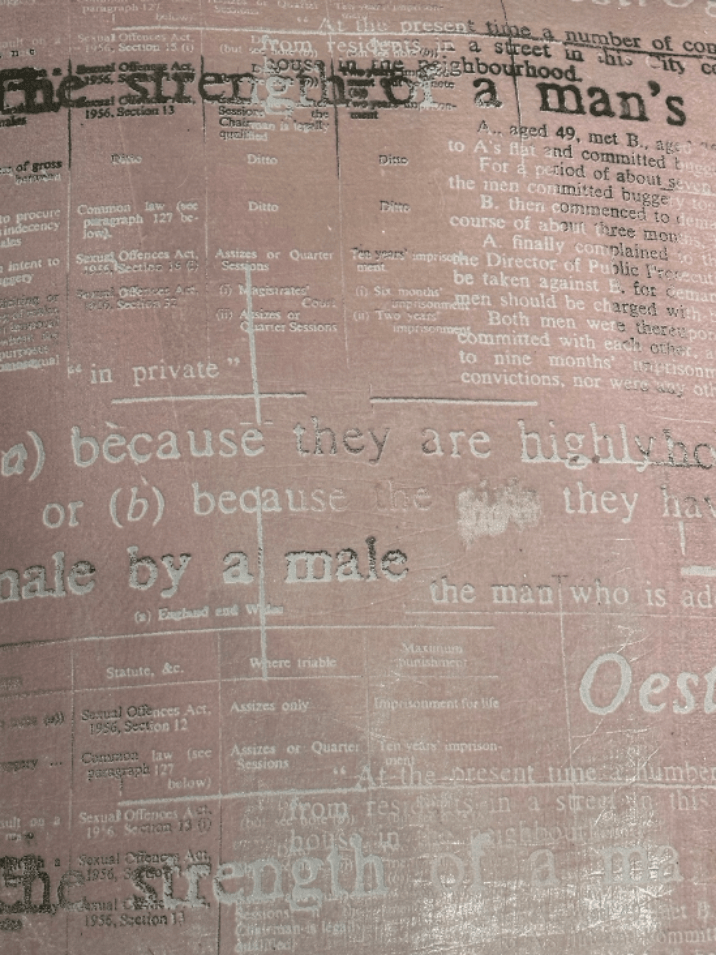

Indeed, the exhibition shines most when it creates a presence of absent lives by means of the literal furniture, décor (take the velvet pillow, screened with the criminal charges directed at gay men from the Wolfenden Report of 1957, covering a statue’s genitalia), and objets d’art (consider the vase of the erōmenos Ganymede surmounted by an aquiline Zeus and the golden phalli peppering an earthenware plate, bowl, and vase) that would have been used, designed, and, above all, enjoyed by Mann’s subjects, making manifest and legible queer identification, desires, and dispositions.

The enmeshment between fin-de-siècle queer desire and the desire for queerness’ perceived decadence to be athetized is emblematic in Acts of Gross Indecency, whose blue-green tiles recollect the charge levied against men in England from 1885 onwards. Reminiscent of those found in public toilets, the anodyne seriality of the titles offers us a deflationary account of the accusation’s gravity while simultaneously coaxing us into awareness of the clandestine water closet as one of the few spaces available for queer intimacy to reach erotic fulfillment. In turn, we are left to imagine the embossed and capitalized indictment unfurling before the eyes of the men amidst their their liaison or their arraignment in a court of law. Mann’s choice to ensconce the tiles in an antique frame only furthers the façade of decency dissonant with the charges brought forth.

Mark Mann, Acts of Gross Indecency. Cast terracotta tiles in an antique, wooden frame (67×50.5 cm). Photograph: © Mark Mann.

Another piquant example of queer interiority is Desire, a dusty rose-hued chaise longue, eye-catching for its color alone and catalyzing sustained interest when the viewer fastens their gaze upon the manually screen-printed text. Like the aforementioned silk pillow, the words in Desire come from the Wolfenden Report, which was instrumental in decriminalizing homosexuality in England. Again, the dissonance between the delicacy (or abrosuna, to nick language from Sappho) and comfort of material items and the treacherous, discomforting terrain of queer pasts is foregrounded in this object of supine recumbence. Once more, it isn’t to be lost that the chaise, ontically redolent of the drawing room’s otium and daydreaming, precludes that very joie de vivre by way of its skeins which run under the would-be recumbent. It, like (queer) life, is no bed of roses.

Mark Mann, Desire. Wood, screen-printed devoré velvet chaise longue (76x71x63 cm). © Mark Mann. Image: Alex-Jaden Peart

Post ‘A Room of One’s Own’, I couldn’t stop thinking about the National Theatre’s recent (and similarly colorful) production of The Importance of Being Earnest. Fulsomely appliquéd with queerness, the gemini lives of Algernon (played by Ncuti Gatwa) and Jack (Hugh Skinner) start to unravel thanks to their amatory pursuits of Gwendolen (Ronkẹ Adékọluẹ́jọ́) and Cecily (Eliza Scanlen). Plots are contrived and feelings dissembled, and the tale, its leitmotif of deplorable modernity circling about, instantiates a stark bifurcation between queer interior and ‘straight’ exterior. And, while a farcical comedy, Wilde’s play is inextricably entwined with the discourses of his time; these very mores precipitated Wilde’s downfall just weeks after Earnest’s première (the father of Wilde’s lover, the earlier Douglas, brought a suit against him, which resulted, ultimately, in the writer being arrested on charges of sodomy and gross indecency). In approaching the anti-homophobic tenor of Wilde’s final drawing room drama, literary critic Christopher Craft saw it achieved by the ‘flickering presence-absence of the play’s homosexual desire, as the materiality of the flesh is retracted into the sumptuousness of the signifier’ (1990: 27). Thus, both Earnest and ‘A Room of One’s Own’ traffic in desiderata, their inhabitants suspended in the untimely purgatory of the queer interstice.

Mann’s exhibition—in pouring itself between the crevices of modern and ancient, between polychromy and achromy, and the infinite regress between queer want and queer lack—makes a very special case for the politics of recognition. We often deem it deeply unsexy to consider ourselves alien. Yet, there are many and considerable constraints upon how much and how well we can know ourselves. I, for one, have not resolved my own mind-body problem.

Nonetheless, ‘A Room of One’s Own’ invites us to consider how we may, at least in the material comforts of the queer interior, possess a sovereign, inalienable right to declare ourselves to be something, to know ourselves, and for our manifestos of self to be taken as indubitable, dispositive, and as strong as an oak. Mann gives us a very powerful vision of existence, one in which we may be the author of ourselves, rejecting the fictive dreams of others and waking up in a room of our own making.

A Room of One’s Own. An exhibition of contemporary queer art by Mark Mann is on at the Museum of Classical Archaeology until 4 April.

By Alex-Jaden Peart