Art by Troy Fielder

At The Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, a neon installation lights the museum’s portico. Multiple English translations of the last lines of C. P. Cavafy’s poem, Waiting for the Barbarians, ask in bright white, “So now what happens to us without barbarians? Those people were a kind of solution” or, through their glow, state; “And now what’s to become of us without barbarians. Those people were a solution of sort”. The reflexivity of the neon signage which jumps from question to answer and back again, and its placement at the front of the museum, sets the stage for Glenn Ligon’s latest exhibition All Over the Place.

A ‘unique intervention’, according to the museum’s website, All Over the Place re-orders the Fitzwilliam’s permanent collection: paintings are re-hung, furnishings are re-arranged, and whole rooms are re-made. For example, the standard order of the flower galleries is interrupted with the effect of questioning the collective and individual authority of the paintings. Ligon’s neon installation and re-positioning of paintings appears as a disruptive fashioning of the museum – they are points of intervention that re-model and re-make the site into something new. This disruption challenges us to question the power structures that are implicit within, and perpetuated by, the ‘ordering’ of the museum’s collections.

Ligon’s interventions primarily take place on the top floor of the museum, as well as in the European and Japanese porcelain gallery on the ground floor. Ligon’s reasons for intervention are outlined in red and white signage which can be found throughout the exhibition. His central preoccupations: ‘race, sexuality, and the role of history’. In his practice, Ligon’s interests may, in their vastness, appear unfocused, yet they hint towards a totality in his vision, a belief in the interconnectedness of past, present and future and the tension that arises from this historical confrontation.

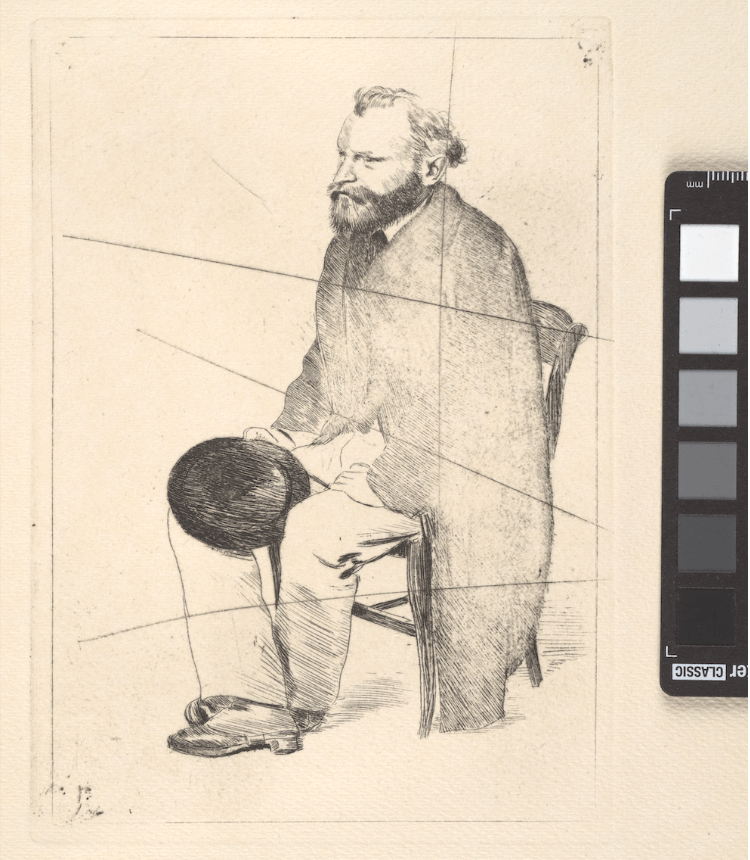

Edgar Degas, Manet assis à gauche [Manet seated to the left] c. 1864–5. Etching and drypoint, impression from cancelled plate

© The Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge.

As I walked into the room that exhibits Ligon’s work, alongside printed etchings by Degas, I immediately felt as if I’d arrived at some kind of centre – a point where place felt significant. In the narrow gallery room, surrounded by wood panelling, place is both anchor and dialogue. The nimbleness of Degas’ drawing of a ballerina, the sense of uninterrupted life, stands in contrast to the ‘cancelled’ plates opposite: once a set of prints has been completed, etched plates will often be marked with an ‘X’ to mark the end of production; in this room, we find X-marked prints from Degas positioned next to prints from Ligon’s own cancelled plates. Ligon’s use of Zora Neale Hurston’s writing in both of his prints – ‘I do not always feel coloured’ and ‘I feel most coloured when I am thrown against a sharp white background’ – and his decision to repeat the quotes in a cream colour that becomes illegible towards the end is at all times facing Degas’ solitary ballerina. Through this combination of artworks, Ligon generates a sense of shared liveliness between Hurston’s writing and Degas’ ballerina. That both the prints and the drawing resist cancellation, that they sit across from each other despite the X’s that mark them creates a sense of continuity, an ongoing resistance to those forces of history which seek to erase.

In the same room, Frank Auerbach’s various sketches – ‘Standing Figure’, ‘Reclining Nude’ and ‘Nude in Profile’, initially went unnoticed. These sketches, exhibited inside display cases in the middle of the gallery room appear as stark and arresting works that connect, or rather intervene, with the works of Ligon and Degas on the walls of the gallery. This intervention posits a sense that the works of art on the wall might have a shared quality, possibly one that could be found in Auerbach’s sketches. These then appeared to me to be amalgams of the works on the wall, points at which severity and lightness could meet. Through this meeting, we see the composite ambitions of All Over the Place: the re-siting of works from the permanent collection, and their interactions with Ligon’s own work, both re-vitalise and re-historicise the works – in one room, Degas, Neale Hurston, and Auerbach enter into an unlikely dialogue.

Study for Negro Sunshine (Red) #15, 2019. Oil stick and acrylic on paper

© Glenn Ligon. Courtesy of De Ying Foundation.

In the Italian, Spanish and Flemish galleries, typically home to works by the old masters, Ligon’s series of prints ‘Study for Negro Sunshine (Red)’ occupy the spaces above, beneath and in-between paintings from the 14th to 18th century. Here, Ligon questions the paintings’ fixed positions in the gallery. By re-ordering their placement, the paintings are moved from some centre that they previously occupied; they are left unbalanced, destabilised. In their place, Ligon’s prints hang – inscribed with the phrase ‘Negro Sunshine’, coined by Gertrude Stein in Three Lives, these red-and-black prints question the normative power of our representational practices: Blackness need not mean darkness, the sun can and should light our visions of the world. To get there, though, we may need to re-view, re-organise and re-balance the places in which history is being made and told.

Through All Over the Place, Ligon offers a vision for renewing the possibilities of a museum – he creates a world in which the mobilities of archives are asserted, where artworks are animated, and where new stories are told.

Glenn Ligon’s All Over the Place is on at The Fitzwilliam Museum until 2nd March 2025.

By Toga Ibrahim