Art by Martha Minton and Troy Fielder.

A neat square cut beneath swaying branches. This is how Martha Minton’s The Stack has stood for the last few months. On 30th September, the structure rose 4 metres from the earth and the final leg of construction commenced. With it, the rain began.

When I meet with Minton, a second-year Architecture master’s student at Jesus College, she is dressed in construction essentials: a hard hat, work boots, and, of course, a raincoat. I am not appropriately dressed. Huddling by Minton’s side as she rearranges stones on the buffalo board floor, acutely conscious of my lack of head protection and the sturdy, though sparse, construction towering above, I get my first glimpse into the realities of undertaking an architectural project of this size.

Minton re-arranges stone flooring in The Stack. Image: Troy Fielder.

Finding its roots in a conversation with Jesus College’s Master, Sonita Alleyne OBE, The Stack is the product of a long-held ambition to host a student-led pavilion, specifically built in the college by its students. Historically, construction efforts of this kind have failed either due to flagging commitment or design disputes. Conscious of the tension that can exist between design and execution, Minton appears to have taken the challenge head-on: pragmatism has formed a central tenant of her design philosophy; construction materials, including the eponymous chimney pots, are sourced by “digging about” around the back of the college’s Maintenance Department.

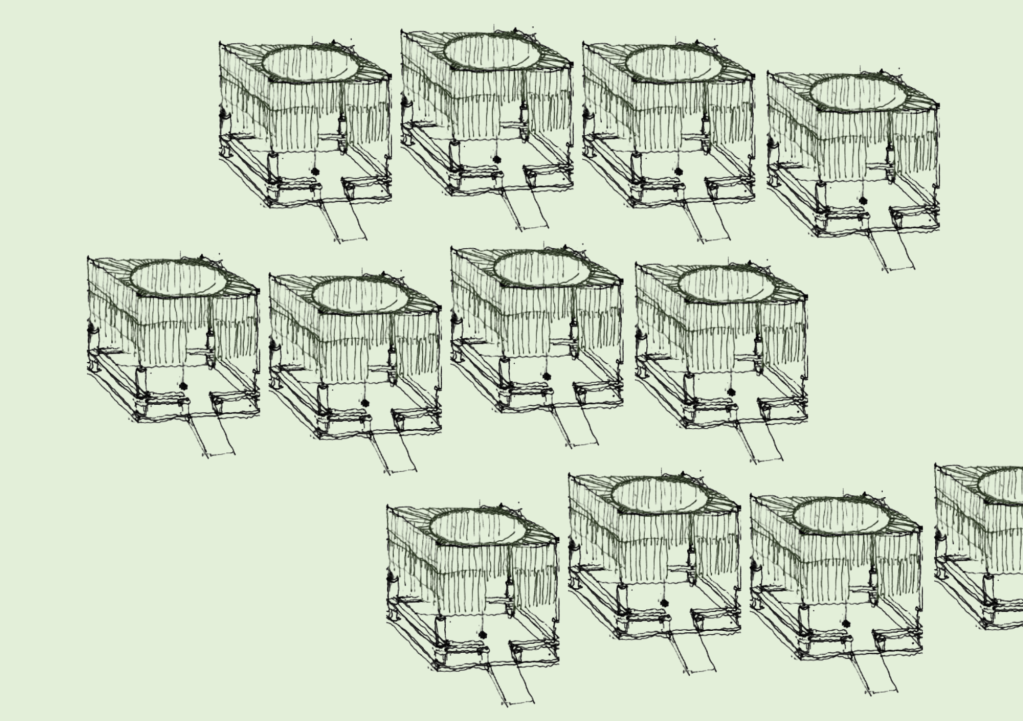

Minton’s architectural practice orients around the re-purposing of construction materials. “A lot of my work is about re-grounding a place,” she explains, “I don’t want anything to go to waste.” In addition to The Stack, Minton is developing a project in Seville that hopes to restore unused and abandoned structures into functional pieces of architecture. One aspect of the project is the removal of bricks from old bottle kilns to make benches for the public. Minton shows me her concept art for the project: an oil painting depicting a child, an adult reading a newspaper, and a pigeon each finding uses for the new set of benches — a multi-generational, multi-species meeting. Clearly, Minton hopes not only to put old materials to new uses but also to inspire novel interactions through her work.

Chimneys for Pigeons Make Benches for Us. Image: Martha Minton, oil on board.

Drawing together abandoned stones and bricks, unused sapling tubes, and the eponymous chimney pots, The Stack is an open-roofed structure made of thick wooden beams that have been joined by bespoke iron brackets. The floor is marked by two parallel rows of red brick that are separated by a thick central line of grey, rough-cut stone. The only interruption to the neat lines of brick and stone is a small circle set in one corner.

“I want it to be messy,” Minton explains, “I kind of want the bricks to wobble on the floor.” She continues, “On my old cycle to work, there was this one junction in Bermondsey where the cobbles made a clicking sound as you ran over them. It gave me a little bit of joy in the morning.” A mundane sense of joy is something that Minton wants to recreate with the pavilion: she is conscious of the public nature of her artwork and wants it to be a place where people feel empowered to go and sit, contemplate, relax. The discovery of the twelve chimney pots was not just stylistically important — their hand-thrown nature inspiring the small “perversities”, as Minton calls them, that litter the project — but also fortuitous: “I thought that they were the perfect size for benches.”

Guests enjoy benches made from previously abandoned chimney pots at the launch of The Stack. Image: Martha Minton.

Beyond the re-use of available materials, the pavilion’s design took inspiration from site-specific cues. Visually, the trees above have been made the main focal point: “the special thing [about the site] is the canopy.” Alternate rows of light green sapling tubes hug the upper half of the pavilion. Standing inside of it, you can’t help but look up through the coloured light towards the sky.

Despite this project’s upward focus, Minton’s work has historically been interested in what exists at ground-level: “I’m more inclined to go down into the floor, so going up is weird.” She does however point out the relationship between the pavilion’s cubic structure — “this is the smart part”, Minton suggests somewhat jokingly — and the concept of solids that Plato developed in Timaeus. Here, the basic elements were said to be constructed by regular polyhedral particles – an idea which has inspired neoclassical architects such as Étienne-Louis Boullée who expanded geometric forms to dizzying scales. In Timaeus, cubes were associated with the earth. In some ways, then, The Stack finds itself between Plato’s particular and Boullée’s grandeur in an attempt to move earth to sky. Perhaps this is a stretch, but a cube bursting with light seems just as good.

I ask about Minton’s hopes for the pavilion now that it is built. “I want people to feel the floor and look at the trees,” she muses, “go and enjoy it, sit on a bench and look up.”

The launch of The Stack. Image: Martha Minton.

Construction of The Stack was completed on Monday, 7th October 2024. It was built and designed by Martha Minton, with the assistance of Aden Kumary, Darcey Chadwick, Elen Jones, Fathimath Ema Ziya, and Jagoda Zuk – with thanks to Jesus College Maintenance Department (Paul McKenna, Richard Secker, James Irwin (Geordie), and Neville Ames) for materials and construction expertise.

By Troy Fielder