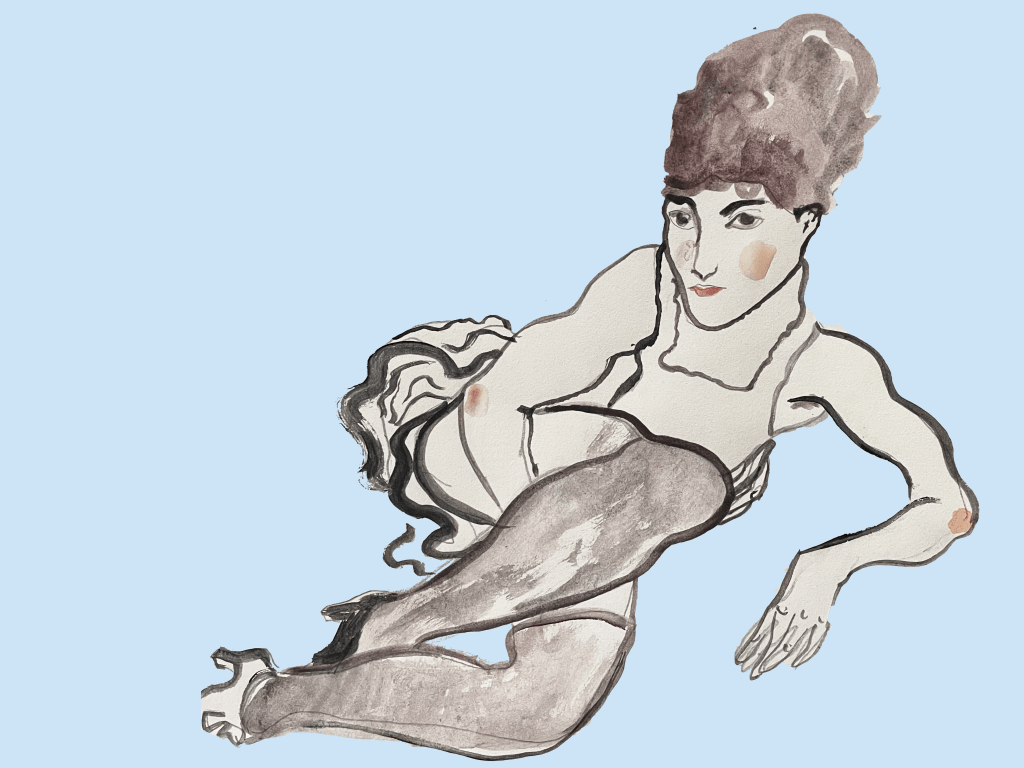

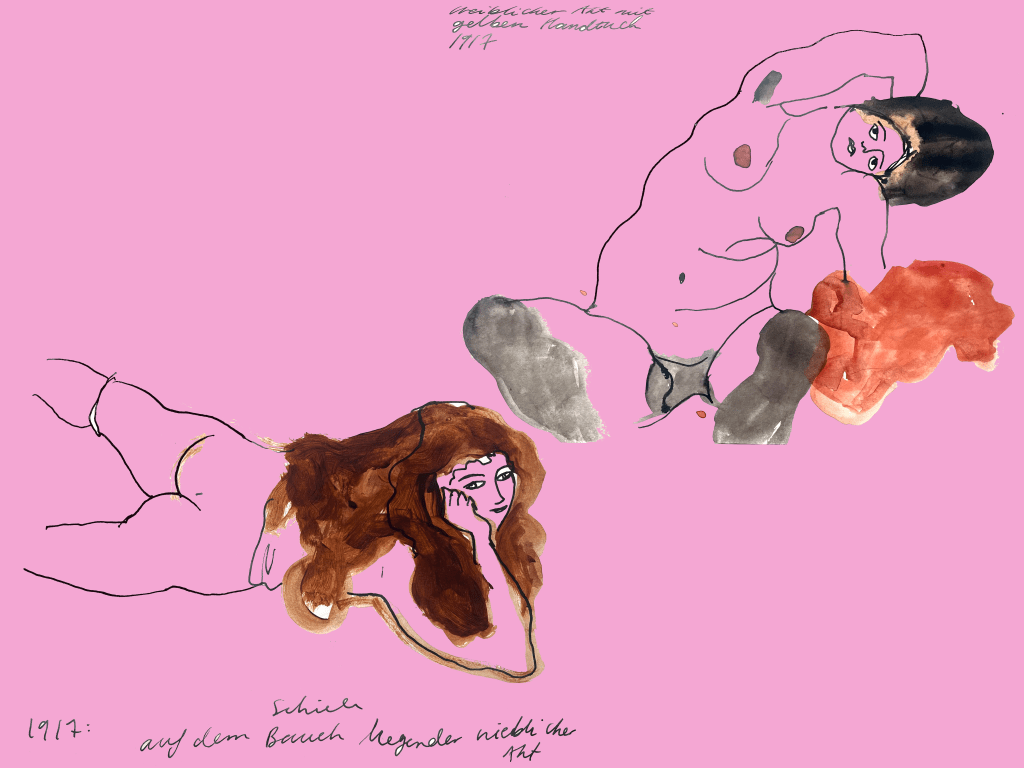

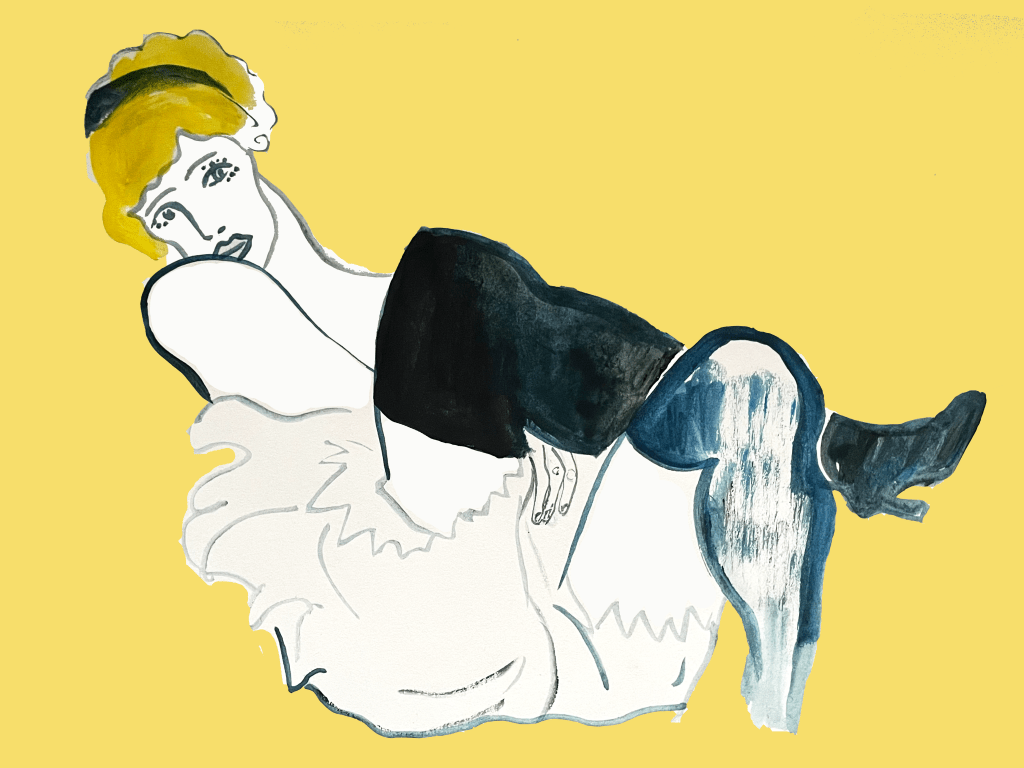

Art by Iris Bowdler.

Sophie Haydock’s debut novel The Flames (2022) follows the story of Egon Schiele’s (1890-1918) four muses — Adele, Gertrude, Vally, and Edith. It is a historical reworking of their overlooked perspectives: the depth and ferocity of their experiences being embroiled with and betrayed by the Viennese protégé of Expressionist art, whose portraits have earned him long-standing fame. Haydock pays heed to the untold, acknowledging the complexities of these relationships, which manifest with particular poignancy in a society torn between radicalism and tradition, between inequality and progress.

It was a December evening last year, in an old Devon barn, when I first met Haydock. I was attending a writing course where she was the guest speaker, and for more than two hours she held the attention of everyone. That evening, she read from The Flames and shared insight into her creative practice, her intentions in writing the book, and the discoveries she made when researching the lives of the four women. In the following interview, a subsequent conversation that we had earlier this year, her sensitivity to the intersection of love, pain, and delusion at the heart of these women’s relationships with Schiele is clear. These were entanglements defined by moral greyness, by deep cruelty, and unhealthy passion. Yet, despite this, love persisted, and it continued to persist through tragedy and sorrow. These are the nuances that are brought into acute focus by Haydock, her four-perspective novel voicing the female lives that surrounded Schiele in intimate detail for the first time.

How did you come to fiction writing? Was it always an ambition, or something that coincided with learning about Egon Schiele’s story?

I had the idea for The Flames in an art gallery — at an exhibition of Egon Schiele’s most radical artworks, at the Courtauld Gallery in London. I was a journalist at the time, and certainly felt a pull towards writing fiction. I was, perhaps, subconsciously, looking for an idea. I’d known a little about Egon Schiele (I knew he was a controversial Austrian artist who lived in Vienna at the turn of the 20th century), but what I saw that day affected me deeply. I learnt details about Schiele’s life that shocked me, and details about his young wife that I found heart-breaking. I knew immediately I wanted to write a novel that shone a light on her story and tragic death [she died from the Spanish Flu in 1918, six months pregnant, aged just twenty-five]. Later, when I started research, I quickly found other women who had been deeply embroiled in Schiele’s life and art, each of whom had experienced tragedy as a result. As Schiele’s muses, these women had been seen, rather explicitly, for more than a century, but their sides of the story had never been told. I wanted to rectify that. The result was The Flames: a novel about Egon Schiele through the eyes of the four muses who loved him.

Why was it important for you to hone the story on the experiences and perspectives of the women as opposed to Schiele himself?

History all too often records the narratives of men, those whose great works and epic advancements so often hinged upon the efforts of forgotten women. I felt, particularly in the context of Egon Schiele and his artwork, that the male gaze needed to be subverted.

In light of what you found out about Schiele and his interactions with the women when researching the book, what is your perspective on him? How do you respond to the problematic aspects of his character, to the moral dubiousness of his actions?

Schiele was a complex figure, and my perspective on him evolved throughout the research process. It’s important to remember that he was a young man when he was creating his most controversial artworks, and if he’d lived another fifty years, I’m sure he’d have matured emotionally and our opinion of him and his art would have shifted, too. He was about to become a father when he died [he died three days after Edith, aged just twenty-eight, also from the Spanish Flu] and that may have changed him. While he possessed artistic genius, his personal relationships were certainly fraught with complexity and sometimes harm. But I wanted readers of The Flames to make up their own minds about him and his actions.

On your website, the book is described as ‘a story of how we hurt those we love the most, and the danger of our delusions’. I find that idea extremely interesting. I’d love to understand more about your thoughts on the combination of pain or cruelty and love, as well as perhaps how delusions can sustain a harmful love or relationship, and what you think these delusions looked like for Schiele’s women. Do you think the hurt caused by love comes from the emotion itself, or perhaps its incompatibility with day-to-day reality, its having to give way to pragmatism; like when Schiele left Vally to marry into wealth, for example?

The intersection of love, pain, and delusion is a central theme in the book. I believe that Schiele was a charismatic and flawed young man who was willing to sacrifice everything he loved — all those he held closest to him, as well as his own sanity and freedom — in the pursuit of his art. I don’t think there was any other way he could have operated, even if he’d wanted to. And this came at a huge cost to the people who dedicated themselves to being with and supporting him. In terms of delusions, I feel that the women around him, at times, deluded themselves about their ability to save him, or themselves, or weren’t honest with themselves about their motivations or the potential consequences of their actions. This had tragic consequences for all involved and is perhaps a message to think carefully and deeply.

What was something that surprised you in the process of researching and writing the book?

I was very surprised to discover, during my research, something that had never been in the public realm before. When I travelled to Vienna to research the novel, I was keen to visit the graves of the four women I’d written about. But there are few records — and I couldn’t find where one of the Harms sisters had been laid to rest. It was by studying the grave records of Ober Sankt Veit in Vienna that I discovered that Adele had actually been buried in the same grave as her brother-in-law, half a century after his death. This was hugely shocking and raised many questions. Why had she been buried there, not with her sister, especially as Schiele’s grave is a protected national monument? Did it support my theory of a love triangle? What’s most saddening is that there was no marker for Adele. Nothing to indicate that she’d lived, or died on 9 May 1968. It’s something I hope to see rectified one day.

What do you think contemporary literature can contribute to understanding and vivifying forgotten histories?

As a journalist and as an author, I’ve dedicated my writing to shining a light on stories that would otherwise go untold, mostly from women who have been overshadowed by more dominant male figures — the “geniuses” who get commemorated by history. By giving these women a voice — albeit fictional, in the case of The Flames — it goes some way to centering marginalised voices, challenging traditional narratives, and helping modern readers foster a deeper understanding of the past. For example, when I was a student at Leeds, I had a postcard of one of Egon Schiele’s most famous artworks taped to the wall in my bedroom. I must have looked at that artwork every day for nearly a year, but I never thought to ask the name of the model, or what her relationship to the artist might have been. I was delighted years later to learn about her and help share her story — her hopes and dreams, desires, and disappointments. And it’s been such a pleasure to get feedback from readers saying what a powerful effect that’s had on them, too. It’s an honour to share these women’s stories.

Your next book, Madame Matisse, will do something similar in terms of vivifying an otherwise overlooked female experience. What made you want to carry on with this thread?

Yes, when you start looking under the surface of the lives of these famous artists — men — and see the women who inspired and enabled their greatness, it’s hard not to become obsessed with wanting to share their stories. My second novel, Madame Matisse, which will be published early next year, is about the three women who were central to the life of the very famous French artist, Henri Matisse. They had incredibly complex dynamics, and there was an ultimatum at the heart of his marriage that has never been written about before in fiction, it seems. Almost everyone knows Matisse’s name, but they don’t know much about his wife Amélie or his main assistant Lydia Delectorskaya, or anything about his daughter Marguerite, either. I wanted to change that and bring their stories into the light for a new generation.

Where do you hope to go next as a writer?

I’ve recently started writing short stories, which I’m really enjoying. Mudlarks — about what can be lost and found at low tide on the River Thames — was broadcast by the BBC in 2023. I’m excited to follow this path as the short story is such an exciting form, one that deserves more attention and appreciation. My favourite writers in this field include Shirley Jackson, James Baldwin, and Guadalupe Nettel.

Could you share any advice for aspiring writers, artists, and creatives?

My advice is always to embrace rejection, and by that, I mean, send out lots of knocks into the world — the more the better, and be zen about what comes back. It might be entering competitions, submitting to agents or applying for a residency. Obviously, do the work, be strategic and do the best that you can. But after that, it’s best to move on to the next thing without obsessing too much about the outcome. You’d be surprised by what opportunities can be created that way. And for me as a writer, that has been key to making progress.

The Flames by Sophie Haydock is available now. For more information, visit Haydock’s Instagram account, @egonschieleswomen, or her website, sophie-haydock.com. Mudlarks can be listened to here as part of the BBC’s Short Works series. Madame Matisse will be published by Doubleday in February 2025.

By Caitlin Kawalek