Art by Iris Bowdler.

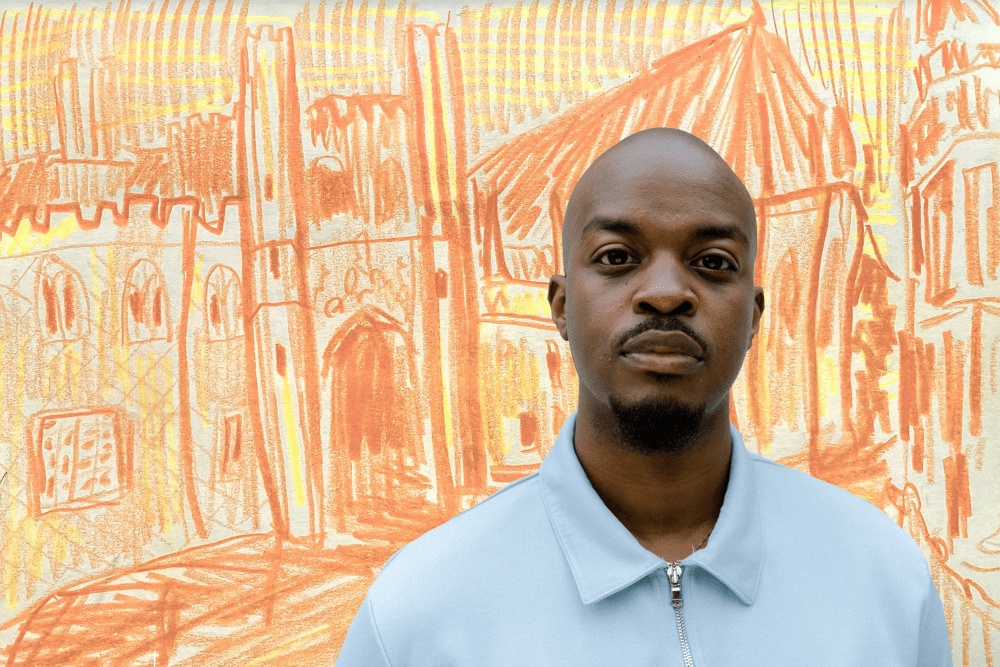

I meet George Mpanga, better known for his stage name George the Poet, at the Old Divinity School of St John’s College, Cambridge. After graduating from the University of Cambridge with a degree in Politics, Psychology and Sociology in 2013, Mpanga is making a return to his alma mater to speak not only about his poetry and activism, but also about the publication of his memoir Track Record: Me, Music and the War on Blackness. He says about the memoir, “a lot of work went into this, a lot of life went into it”.

What’s it like being back in Cambridge? “As much as it changes, it stays the same,” Mpanga tells me. “Just looking at the place with older eyes, travelled eyes is always interesting.” During his degree, Mpanga’s love of poetry and rap burgeoned and within two years he had signed a record deal. Since then, his career has skyrocketed: in 2018, he was elected as a member of Arts Council England and, later that year, he opened Prince Harry and Meghan Markle’s wedding with a reading of a love poem. In 2019, his podcast, Have You Heard George’s Podcast?, was the first outside the US to win a Peabody Award. Earlier this month, he performed alongside Kae Tempest and Sophia Thakur, amongst others, at the Royal Albert Hall as part of the ‘Poet’s Revival’.

At the heart of Mpanga’s work lies a concern with the historic silencing of, and social and economic violence against, people who have been racialised as Black — as well as a mission to shine a light on the long history of Black artistry and creativity. In April, this work coalesced in the form of his memoir: a blend of private and public histories that range from stories about his time at Cambridge to attempts at unpicking the complex legacies of colonialism. “Blackness has a rich history that we are all part of,” Track Record explains. “[B]y reflecting on our condition using Black cultural works, we can study and document our own track record.” When I ask Mpanga about the role of the poet in this process of documentation, he reflects on poetry’s ability to reach people on an emotional level: “I think the poet can bring some humanity to the story. We’re inundated with updates, news, and so-called analysis, but someone needs to do the job of putting some colour into the picture, putting some feeling into the picture.”

However, Mpanga is wary of the poet’s propensity to individualise, to move their gaze away from society: “this feels like a time where we need to be talking more about the world than ourselves, as poets, because so much is going on.” Our responsibility to our communities, to something bigger than ourselves, is a theme that recurs throughout our conversation. “If we try and think at a community level, we’d be able to think more critically about the needs of our community, instead of just forming smaller and smaller units that become opposition.” How, then, does he resist this temptation to individualise? “I think the way to combat that is to just be accountable to people just as I’ve explicitly done throughout my work. To say, look, this is where I have derived benefit from being part of a collective — I rely on society and, therefore, I have a responsibility to care about what happens to everyone.”

As his success and fame have grown, Mpanga’s ability to stay in touch with the communities that he so passionately defends has, at times, been difficult. At one point, he states, “I felt optimistic, fundamentally optimistic about the direction of the country and the world — and I felt alienated from a lot of the anger that was being expressed in the public space”. Increasingly, Mpanga became aware that his celebrity status might be warping his perspective. “I was starting to develop an oversimplified idea of what success was,” he reflects, “and becoming a bit detached from the day-to-day experiences of people.” To combat this, he felt that he needed to take his work in a new direction: “Sometimes you need to be jolted out of it. Sometimes you need an unceremonious reminder, you need a rude awakening.”

It’s unclear what this rude awakening may have been for Mpanga – if, indeed, it needed to happen – but in 2021, under the supervision of Professor Mariana Mazzucato and Dr. Karen Edge, he began a PhD in economics at University College London. “I think the rigour of a PhD is something that I needed intellectually,” Mpanga explains: “politically I was unfocused, but the PhD has forced me to get focused.” His thesis takes an economic lens to explore the social and political value of Black music. The advantages of this pursuit are clear to him: “In the PhD you have to try and be surgical in your analysis and your argument, in your awareness of the discourse, [you have to] really brush up.” However, “I don’t think you necessarily have to go to a university, do a PhD, to do that,” Mpanga continues. “I think you can challenge yourself throughout your life to develop a perspective that allows you to contribute something meaningful to some of the important conversations.”

What role does music have in the current conversation? “[Music] is the purest expression of youth. Emerging styles, even if they’re not necessarily speaking directly to the direction, just the energy, just that excitement, […] whatever the kids are working on, I try to take an interest.” To get into the industry, Mpanga would encourage young people to “tap into [their] network, sell people on the vision, develop a vision that is people-centred, and invite them in. If it’s something that serves people, it will develop a life of its own.” Taking a look at Mpanga’s career to date, it’s clear to see that he has benefitted from this advice: his vision and ambition continue to grow — taking a life of their own — and show no signs of slowing.

George the Poet’s Track Record: Me, Music and the War on Blackness (£22) is published by Hodder & Stoughton, released April 2024.

By Troy Fielder.