Art by Elizabeth Murphy.

Born in London in 1993, Tom Fairlamb has spent most of his life between Newport, Glasgow, and Colorado. Fairlamb began a degree in Maths at the University of Glasgow, before leaving in his second year; he retains a fascination for the philosophical side of the subject. For the next two years Fairlamb worked in a bar, before the feeling of stuck-ness made him seek change. Taking advantage of his dual citizenship, from 2015 to 2019 he moved to Denver, Colorado (experiencing the ‘surreality’ of the Trump era) where he spent his days visiting galleries and hiking with his new dog, and started painting. Fairlamb (and dog) moved back to Scotland and started putting together a portfolio.

Fairlamb graduated in Fine Art from Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design in Dundee and is currently enrolled in Contemporary Art Practice at the Royal College of Art in London. In April, he was shortlisted for Bloomberg New Contemporaries (2024), and is the recipient of numerous other awards, including The Royal Scottish Academy Stuart Prize (2024).

Fairlamb’s works are various, protean things; he makes durational, moving sculptures which blur into other media such as performance, video, painting, and drawing. The works are suggestive, decidedly open to interpretation. Fairlamb describes his previous work as “focussed on themes of the human condition in relation to technology.” More recently, his work has been guided by posthumanist ideas. “By observing the world’s cycles and processes, he simulates interactions and connections between nature and technology, questioning the impact of the categorisations and boundaries we create between human and non-human worlds.” His works shift between elegance, bathos, exhaustion, and muted hopefulness, as you stand, quite human, at their side.

I encountered Fairlamb’s moving sculptures by chance while visiting Edinburgh. Struck by his works, I contacted him for an interview. Unable to meet in person, we mutually decided on a slow, thoughtful email exchange; a certain apposition surrounded our discussions of imbricated systems and technologies.

‘It Didn’t Used To Be This Way’ (2024). Image: Tom Fairlamb.

Do you have a favourite work (of yours)?

It’s maybe a bit cliché but my favourite work is what’s next. This new project feels very different. It feels more like drawing — but the drawings are built with electrical wire and hooked up to a battery to supply energy. It’s a little scary to me, but I think that’s a good thing. Of my finished work, I like them all for different reasons — it’s like choosing your favourite child. In the past I’ve found it easier to like works that include elements of chance — perhaps because they feel a little more removed from my creation, so they become easier to admire. For that reason I like ‘It Didn’t Used To Be This Way’ most right now. I find the unpredictability of the butterfly’s movement interesting.

Yes, in ‘It Didn’t Used To Be This Way’ (2024) there is a sense of the work’s agency, its dislocation from artistic mastery. I like that idea of chance. Is this chance element related to your interest in posthumanist themes? Could you talk about what posthumanism has meant in terms of material as well as conceptual changes to your work?

I’ve been interested in chance and unpredictability for as long as I’ve been interested in art, so it’s not really derived from my interest in posthumanism — but it was one of the first steps in realising my interest in philosophy. Posthumanism as a categorisation only came to me after I discovered many of my interests and beliefs fell under that title. I’m intrigued by subject-object relations, where agency lies. That was the first thing that got me interested in using everyday objects and movement. I’m also interested in the decentring of the human — viewing ourselves as just another part of the larger ecosystem. Of course, a lot of these ideas are thousands of years old, mostly originating from eastern cultures, but they also fall under the category of posthumanism. This was why I decided to move away from making figurative work which focused on the human body. My work still retains the human, but it isn’t as large a part of the focus now.

Many of your works necessarily feature cables. Cables are often hidden, but you make a virtue of their sprawling forms. What’s your conceptual-artistic response to junk, clutter, extraneous matter?

I’m not often a huge fan of extraneous matter in artwork to be honest — clutter can work well if there’s a reason for it, but at that point it’s no longer extraneous. I like to keep the wires for transparency. I think there’s an element of magic in the works, but I don’t want them to fool or trick necessarily. And the wires add to the visual surge of energy that connects all the works. You can see that they are plugged into the mains grid and the same energy source is powering them all: there’s a collectivity to it.

In many of your works, non-human bodies are trapped, unable to metamorphose, to travel, to leave. Yet still they flicker, flutter, resisting the systems in which they find themselves imbricated. How much do you think about technological systems alongside, as you mentioned earlier, the larger ecosystem?

Technology is a broad topic. It’s often registered in terms of modern technology, like phones or computers, but it can be considered as a term much more broadly. A bird’s nest is bird technology. A horse pulling a cart is a form of human technology — especially since horses are often bred to suit a certain need. I think that technology emerges from an urge to try to change and adapt the world to better suit oneself. I’d say it’s as natural as anything else. Technology evolves and adapts just like “the natural world”. It’s often considered as separate from “nature” or “the natural”. But humans are organisms and a part of the larger organism — Earth. What we do and make is an extension of ourselves and therefore an extension of Earth. But I don’t want to seem totally pro-all-technology. I think it is very important to think of the consequences and agency that our creations have, to try to be conscious of what we put out into the world.

The invisible string used in ‘It Didn’t Used To Be This Way’ is entirely imperceptible to the viewer. How difficult is it to work with?

I’m glad that you said that because for the RSA show I doubled it up and it became more visible to me. I had tested it before but as it was a month-long show, I worried it wouldn’t last. And on the install day someone snapped it, so I decided to double it up so it wouldn’t be a problem. It’s difficult to work with — you can barely see it or feel it in your hand. I got quite a few funny looks in the studio trying to tie it. It must’ve looked like I was practising a mime act.

And why did you choose desk fans instead of, say, heating ducts, an industrial fan, or a hot stove?

The use of desk fans came from older work and has become part of my palette of objects. I was interested in using everyday objects, especially ones from domestic and office spaces; for me, they speak to the work/leisure balance of contemporary life. I think of the desk fan as the quintessential form of fan — it’s what I imagine when someone says ‘fan’ and that’s important to me. It stops the idea becoming distracted or diluted. I also like the movement of oscillating fans. As well as their blowing, placing them on their backs creates this sort of writhing motion which really animates them.

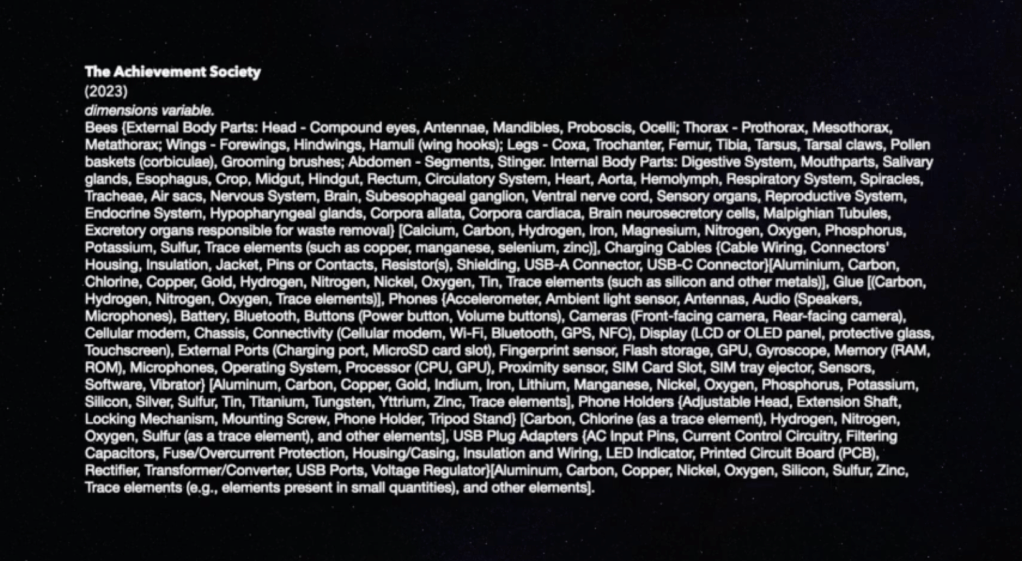

In ‘The Achievement Society’ (2023) dead worker bees are attached to phones; the phones loop a video of simulated flight, suggesting the bee’s progress from flower to flower. Not only in this work but in all your works shown at the RSA I was struck by their (apparent) simplicity. Yet the list of mediums listed in the work’s descriptor is prodigious. Could you develop this tension between simplicity and complexity?

To me a work’s successful when it has simplicity but isn’t simple. The idea behind the list of mediums was to question what we decide as individuals. The work is one sculpture, but it’s made up of components, one of which is a bee. But the bee is also made of components and those components are made of components — at what point do we draw the line? I took the components right down to the chemical elements. At that point you notice that all the sculpture’s parts are pretty much composed of the same core elements. After writing the list I noticed that a lot of the components of the phone were that of the bees. I found that interesting: how we use words, how we name things.

‘The Achievement Society’ (2024). Image: Tom Fairlamb.

And, very recently, this work was stolen from the RSA. I wonder how you’re feeling about the work, its absence, and what its absence means?

The theft was a strange thing to happen. I’ve shown that work at less secure spaces, so I really didn’t expect it to go missing from the RSA. Disappointingly, it wasn’t stolen on merit but material value — maybe my sculpture even devalued the phones… The title of the work was taken from a book called ‘The Burnout Society’ by Byung-chul Han, which considers our excessive work culture, how we commodify our free time and leisure activities. The piece depicted worker bees endlessly collecting pollen — it’s an interesting thing to have happened to that work specifically. I suppose the person who took them was just a little bee who really needed some pollen.

‘The Achievement Society’ (2024). Image: Tom Fairlamb.

The title of your work ‘The Current Current of Current’ nods to electrical, aquatic, and temporal currents. The title itself seems to be a poem, a kind of monostich. You mention that ‘The Achievement Society’ was inspired by ‘The Burnout Society’ — how much of a role do words, labels and titles play in your practice? And more broadly, how much of a role does literature play in your practice?

I like to think of titling as another object or material in my work. It can be used to direct pathways of thought and attention. Sometimes it comes easily. Other times, I have a huge list and narrow it down to just one. For ‘The Current Current Of Current’, I wanted the title to be open yet additive. I also liked that it was a bit humorous. Humour has been a big part of my work in the past. This body of work is less humorous, but there are still elements in the works’ absurdities. Literature is a great source material for ideas. I take a lot of inspiration from other artists, philosophy, and non-fiction. When ideas are written down it’s easy to translate them visually while still having something that feels new and exciting.

What are you excited about right now?

I recently read The Overstory by Richard Powers and The Vegetarian by Han Kang, both about humans and their relationships to trees — I feel very inspired by them. But I can’t force my work in directions: it leads me places. I either make a work then research related topics, or I research something that interests me, then months later I’m making something related. I work in a rolling process where the work and research both feed each other.

‘The Current Current of Current’ (2024). Image: Tom Fairlamb.

By Matilda Sykes.

Images and words from Tom Fairlamb and the Royal Scottish Academy.