Art by Iris Bowdler.

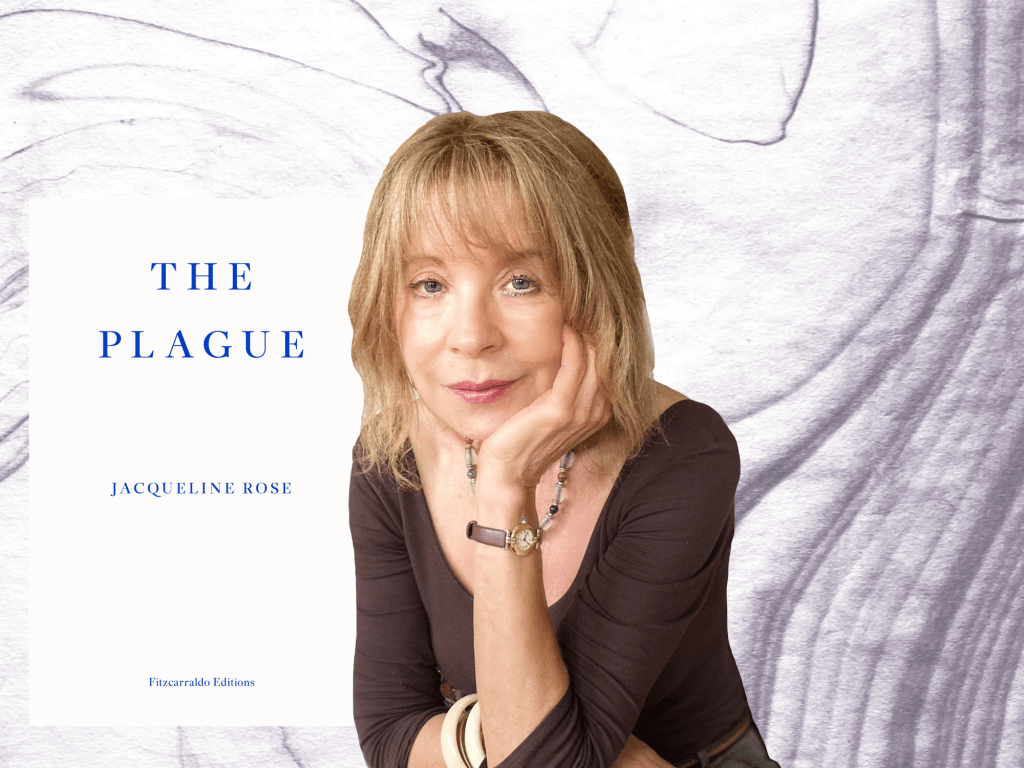

Jacqueline Rose’s latest book is fittingly haunting. The Plague: Living Death in Our Times was written in 2022, published in 2023, and now, speaking at the Cambridge Literary Festival, Rose sees her postulations ripple through — haunt — the last 24 hours: Israel’s retaliatory strike upon Iran, and the extremity of the violence enacted in Gaza, Scotland’s pausing of puberty blockers for transgender youths, and the ongoing “attacks on the humanities” at universities across the globe. In what is nonetheless a hope-filled conversation, Rose demonstrates The Plague’s preternatural awareness of our post-pandemic culture.

I meet Rose at the Gonville Hotel, the day after her talk. Co-director at the Birkbeck Institute for the Humanities, she is a writer and academic whose work refuses to be bound to a singular discipline. Her scholarship incorporates and entwines feminism, psychoanalysis, literary criticism, and political thought. No matter her subject, Rose tells me, her work returns to her efforts for a more just and “psychoanalytically attuned culture.”

Her varied interests have in turn produced a number of politically engaged books (On Violence and On Violence Against Women, The Question of Zion), a novel inspired by Proust (Albertine), and her acclaimed feminist literary study, The Haunting of Sylvia Plath. Yet The Plague is perhaps her most universal and pertinent, configuring and acknowledging death as an “unavoidable intruder into how we order our lives”, while equally refuting the myth that the COVID-19 pandemic served as a “great equaliser” across the world.

The essay collection (titled after Camus’ 1947 novel, which regained a popular readership — including Rose — in 2020), broadly, discusses the mass acknowledgement of death that was required to contend with living during the COVID-19 pandemic. In its dialogue with a number of cultural and psychoanalytic theorists, The Plague also reveals a historical patterning of pandemic and violence as interlacing phenomena, specifically referencing Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. Rose’s work aptly paints the precarious state of the world as it has only continued to dissolve into further unkindness and violence.

Two years on from the completion of her book, in a post-pandemic society where art that tries to talk about the pandemic is sometimes treated as tired, or overly reflective upon a morbid history, Rose reveals that there still remains much to shed light on. The after-effects stubbornly remain in every room and every nation; her work unlocks pieces of a select subconscious that we all share.

The essays themselves comprise “almost an accidental book”, she explains. They move from thinking about Freud’s loss of his daughter in the 1920 pandemic, to the philosophies of Simone Weil as well as Rose’s own conception of “living death”, and the pandemic’s simultaneous “femicide” of domestic violence. Originating from several other, independent projects – such as the 2020 Freud Memorial lecture on the centennial of Beyond the Pleasure Principle – Rose’s essays began to constellate themselves into a book project.

Re-reading Freud in the context of the pandemic helped to surface something new for Rose: “this is theory grappling with pandemic and war,” she explains, “which are the two things which Camus says no society is ever prepared for.” “[B]it by bit I realised that I had been tracking horror, but with a psychoanalytic shadow. That all these writers in these situations, whether through sexual difference and domestic violence, whether through the Second World War in France and what it meant to be an occupied nation, were all touching on both aspects of what, for me, we need to think about social and political life.”

This precarious state of being, its shadowiness, and where the stirrings of hope might find themselves revealed haunts The Plague, and looms over my conversation with Rose. Rose sees psychoanalysis as a broad-scale way to approach our socio-cultural realities: “It’s a question of what’s sayable, and psychoanalysis is all about what is sayable.” This is not necessarily a case of investigating personalities, but “you can certainly spend some time looking at what psychic permissions individual figures release into the atmosphere,” and, to enlarge the subject, analysing the causations and implications of the “rhetoric” of nation states.

She continues that in our current political environment, where “fascistic banalities are being spewed in the public domain”, the “need to allow for the complexity of subjectivity, and the contradictory nature of our political identifications” as the most profound act of resistance.

Our conversation turns to where art falls in this idea of resistance. In 2020, Rose wrote a piece for the Gagosian Quarterly, the modern art gallery’s publication, about COVID-19. “I think it was important that I got asked by the Gagosian to write for them, because they were very interested in the way aesthetic transformation can be a rebuttal.”

I ask her for examples of literature that put this creative rebuttal into practice. She recommends me two: the first is Anna Burns’ Milkman (2018), a Booker Prize-winning novel whose prose is “so taut and innovative, it’s quite remarkable” — “everything is between the covers of this book”; the second, “which still couldn’t be more relevant for now”, is Eimear McBride’s A Girl is a Half-formed Thing (2013), a novel “very much about abuse, but also what it is to be a woman. Charting the waters of your own inner life […]. That writing I find extraordinary, and I’ve sort of clung to those two books, but of course there are others.”

Amidst the precarity she sees all around, it is inspiring that Rose finds a kind of safety in impactful writing. The possibility of writing to provide such security feels connected to her ongoing interest in motherhood; Mothers: An Essay on Love and Cruelty (2018) critiques the expectation for mothers to be stabilising, reparative forces. At one point in her talk at the Festival, Rose likens the state of the world to the crumbling of a mother’s utopia, as, impossibly, “mothers are expected to make the world feel safe and just.” The “fallaciousness” of this expectation is exacerbated in the domestic space during a pandemic: it becomes obvious women can no longer save men from mortality and, in turn, men (and power structures) are enraged.

I ask Rose if a mother raising and safeguarding children, who is attempting to realise that fantasy in spite of the world’s dangers, might be exactly the kind of hope that Simone Weil defines in the epigraph to The Plague: “We are not really without hope. The mere fact that we exist, that we conceive and want something different from what exists, constitutes a reason for hope.”

She suggests I read up on Hannah Arendt’s natality, the idea “that every newborn baby is the possibility of a new beginning”: “you don’t know what that child has brought with it and therefore how it will live. [Arendt] says natality is an inherently democratic moment.” She also admits that we put our hopes in the next generation. That somehow we (young people) need to “link” Arendt’s natality with Freud’s “repetition compulsion” and “haunting” — and “of course, artistic practice.”

It seems to me that banking on hope, and working with it, is not as futile as people like to make you believe. That, like Rose says, the practices of writing theory, making art, or collectivising protest, really are some of the most inspired, tangible things we can do — to dream of, to create, to fight for “something different from what exists” — and to see those things through to the very last of their possibilities.

Jacqueline Rose spoke with writer Marina Benjamin about The Plague as a part of the Cambridge Literary Festival on April 19, 2024. This interview took place April 20, 2024.

By Sarah Jean Abernethy.